|

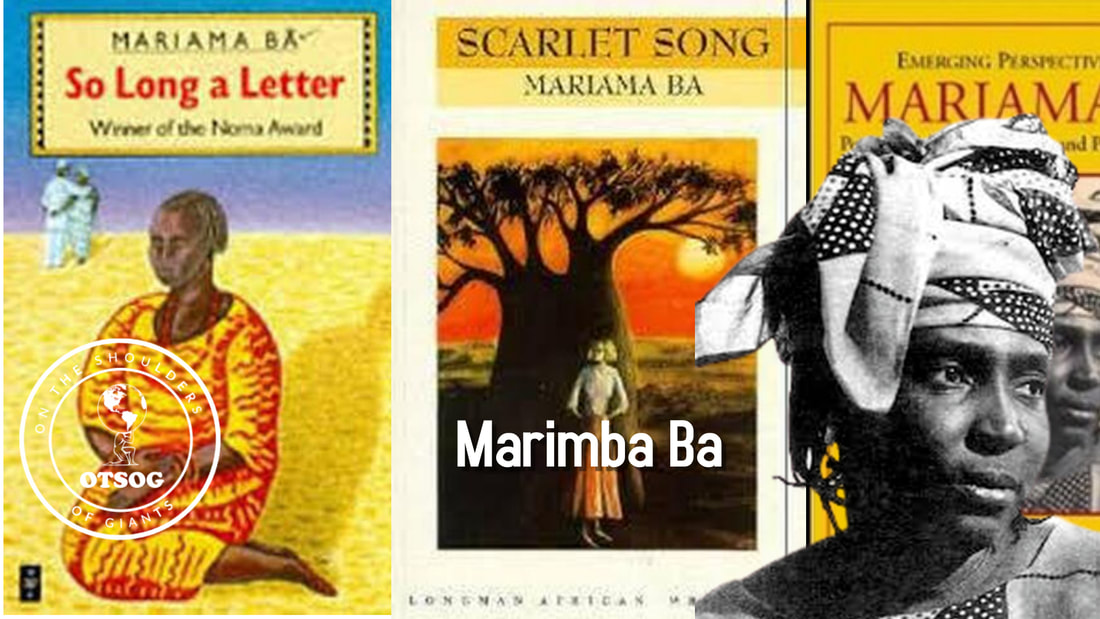

On April 17th, 1929, Marimba Ba was born in Dakar, Senegal, to parents who were educated and prosperous. Her mother died when she was a young girl, and her father became the Minister of Health for Senegal in 1956, he also worked as a civil servant before becoming the minister of health. Her grandfather was said to be a translator for the French during his time. After the death of her mother, Ba was raised by her father and maternal grandparents who made sure she received an adequate education. She was educated in the French traditions coupled with Quranic teachings; her grandparents made sure she learned Islamic values. Ba was an excellent student who at the age of fourteen earned the highest test scores for her age group. As Ba grew older, her thirst for knowledge and education was being challenged by traditional Islamic culture; her grandparents didn’t believe that a young woman should be educated because of their traditions, but Ba and her father held a different opinion about education. Ba’s father backed her decision to educate herself and helped her enroll in the Ecole Normale, or the Teacher Training College in the city of Rufisque, Senegal. She graduated from the training college in 1947 and became a teacher for twelve years. During her time as a teacher, Ba met and married a man named Obeye Diop. The couple produced nine children before divorcing and Ba becoming a single mother of nine children. Ba’s health started to decline during the latter years of her teaching, so she transitioned her career to become an educational inspector for the Senegalese Regional Inspectorate of Teaching. Ba was regarded as one of Senegal’s most exceptional and prized teachers despite her retiring early from teaching. She was later honored for her teaching in 1977 when a school was founded in her name by Senegal’s President Leopold Senghor. Marimba Ba was a single mother raising nine children and able to provide for her family in a society where the men are usually the primary provider for a family. This was also where Ba’s activism for women’s and human rights began. European neocolonialism was continuously spreading throughout Africa and was a threat to the African nations that were newly independent or developed nations. Ba was at the forefront of the fight against neocolonialism and women’s rights in Senegal. Her next move was publishing her first novel titled So Long A Letter in 1979, which became a critically acclaimed and Noma Award-winning novel. So Long A Letter was a novel that gave a history of the contributions of Senegalese women, it was also a peek into the life of Ba and other women in Senegal, and the challenges they faced to exist as women. She used her novels and community work to help fight discrimination against women, along with fighting the racist practices the French implemented in Senegal. In 1981, Marimba Ba died due to complications with cancer. Her second novel Scarlet Song was published in 1986, and similar to her first novel So Long A Letter, Scarlet Song was also a successful novel that focused on an interracial relationship in a traditional Senegalese society. Ba was just as adamant about restoring Senegalese culture before its French and Islamic influences, as she was about fighting discrimination against the women of Senegal. She was proud of her people and her culture. Ba’s third novel, La Fonction politique des littératures africaines écrites, was focused on encouraging African people to be proud of who they are, where they are from, and their own cultural practices. She was unsatisfied with the way the women were treated, and unsatisfied with the forced influences of the French through colonialism. Marimba Ba is the first woman in Senegal to publish a novel, and it was fitting that her writings challenged the oppressive traditions of Senegal against its women, and even against its men due to colonial influences. Ba experienced hardships and successes. She was supported by her father early in her journey, which helped her to be intentional and fearless in her pursuit of freedom and liberation for her people. Marimba Ba, we proudly stand on your shoulders. J.A. Ward Click here to support the On the Shoulders of Giants book series!!! References: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mariama_B%C3%A2 https://www.blackpast.org/global-african-history/ba-mariama-1929-1981/ https://www.sahistory.org.za/archive/biography-mariama-ba-lauren-daugherty https://www.historyheroblast.com/historyhero/mariama-ba

0 Comments

On May 2, 1879, Nannie Helen Burroughs was born in Orange, Virginia, to parents John and Jennie Burroughs, who were formerly enslaved. Mr. John Burroughs worked as a farmer and was also a Baptist Preacher. Nannie was the eldest of the Burroughs’ children; when she was five years old her father died forcing her family to move to Washington D.C. to live with her aunt Cordelia Mercer. The Burroughs family has a history of gaining skills to create income for survival, Burroughs and her mother were able to bring those skills with them to Washington D.C. to make a living. The Burroughs family took full advantage of the plethora of opportunities available for them in Washington D.C. Nannie was a bright and gifted student who shined in her academic studies. Her academic prowess continued throughout her schooling, helping her graduate with honors from M Street High School in Washington D.C. As a high school student, Burroughs was active within her school’s activities. She was the organizer of the Harriet Beecher Stowe Literary Society at M Street High School. She was also able to study business and domestic sciences giving her a number of skills to make a decent living. Burroughs’ fire and determination led her to meet two women who were active within the women’s suffrage movement that inspired her, Anna J. Cooper and Mary Church Terrell. After graduating from high school in 1896, Burroughs sought a teaching job within the Washington D.C. school system; it is said that she didn’t get a teaching position because her skin was too dark. She was denied a teaching position by fellow blacks, but she didn’t allow that experience to stop her from teaching. In 1898, Burroughs moved to Louisville, Kentucky to work for the National Baptist Convention as an editorial secretary and bookkeeper for the Foreign Mission Board. Burroughs was one of the founding women of the Women’s Convention, which helped to serve the National Baptist Convention. She served with the Women’s Convention for forty-seven years and was the president for thirteen years. At the time, the National Baptist Convention was considered one of the largest African American organizations for black women. The National Baptist Convention received help from the National Association of Colored Women to serve black women in America, one of the outcomes of the partnership was the creation of the National Association of Wage Earners, an organization that was created to help black women earn better wages. Burroughs served as the president of the National Association of Wage Earners and Mary McLeod Bethune served as the Vice President of the organization. In addition to being a member of the National Association of Wage Earners and the National Baptist Convention, she served with the NAACP and around six other organizations. Burroughs began working with Herbert Hoover around 1928 to help with black home and land ownership, she also gave her famous speech "How White and Colored Women Can Cooperate in Building a Christian Civilization," in 1938, at the Virginia Women's Missionary Union at Richmond. As a response to her not being able to teach in Washington D.C. and the continued discrimination black women faced in America at the time, Burroughs decided to open her own school for women called the National Training School in 1908. The school started in a farmhouse and gave women who could only take classes in the evening a chance to earn an education. Because Burroughs was such a great teacher, the word spread quickly increasing the popularity of the school, which meant the enrollment drastically increased. Burroughs was using the school to help prepare black women to become the greatest versions of themselves, and in turn, help all of Black America become the greatest version of its self. The school was shaped by their three B motto: the bible, the bath, and the broom. In addition to the skills the women were learning, Burroughs made sure there was an emphasis on teaching black history, so she created her own black history course for her students. Burroughs was preparing the black women of the National Training School to combat the wage labor problems affecting black women, and negative images of black people by the white media. The women were prepared to combat racism, elevate themselves and their race, and do whatever work needed to be done to be able to strive despite being victimized by racism. Burroughs was a popular person because of her efforts to educate and equip black women to be self-sufficient and create a reasonable living, but she was seen as a villain by those who wanted black women to stay silent and only engage in domestic work. Her being rejected by the blacks within the Washington D.C. school system was a blessing in disguise. She was able to help many black women from poor backgrounds who would have been overlooked by the so-called black elite. Her grassroots efforts helped generations of black women find their callings outside of their homes. During the 1920s, Burroughs wrote and published two plays, The Slabtown District Convention and Where is My Wandering Boy Tonight? Nannie Hellen Burroughs died in 1961 of natural causes, leaving behind a legacy of service and commitment to her people. The National Training School was renamed the Nannie Hellen Burroughs School in 1964. During and after her life she was honored by receiving an honorary Master of Arts degree from Eckstein Norton University in 1907, May 10th of 1975 Nannie Helen Burroughs Day was declared in Washington D.C., and Nannie Helen Burroughs Avenue was named after her. To the incredible Ms. Nannie Helen Burroughs, we proudly stand on your shoulders. J.A. Ward Click here to support the On the Shoulders of Giants book series!! References: https://www.nps.gov/people/nannie-helen-burroughs.htm https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nannie_Helen_Burroughs https://kinginstitute.stanford.edu/encyclopedia/burroughs-nannie-helen https://www.blackpast.org/african-american-history/burroughs-nannie-helen-1883-1961/ |

Details

Categories

All

Click Here to join our mailing list

|

Contact Us: |

Connect With Us |

Site powered by PIT Web Design

RSS Feed

RSS Feed