|

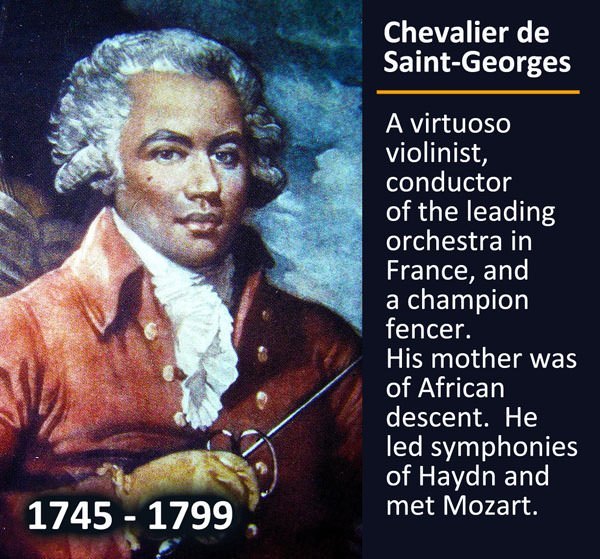

Joseph Bologne, Chevalier de Saint-George was born on the island of Guadeloupe in the French West Indies, on December 25th, 1745. His father was a plantation owner, slaveholder, and nobleman named George de Bologne Saint-George, his mother was a Senegalese slave woman named Anne Nanon, she was the mistress of de Bolonge. de Bologne was particularly fond of Saint-George, he treated him and his mother better than he treated the other slaves he owned. Seeking a better life for his son, de Bologne moved Saint-George and Nanon to Paris, France along with his legitimate family in 1753. Upon Saint-George’s thirteenth birthday he was enrolled into France’s premier fencing boarding academy led by the legendary swordsman Nicolas Texier de La Böessière. Saint-George was a well-rounded student holding interest outside of fencing which included several sciences, literature and horseback riding. Within two years of enrolling into the fencing academy, Saint-George’s progress was fully noticed by La Böessière and everyone at the academy; he was tall, strong, fast and held an uncanny ability to learn quickly. A Fencing-Master named Alexandre Picard decided he wanted to duel with Saint-George, Picard often publically called Saint-George La Böessière’s mulatto as an insult. The match was highly anticipated and highly attended; many people placed high wagers on the swordsman they favored to win. Saint-George would emerge victorious only adding to his legend as a master swordsman. His was rewarded for his victory by his father with a horse and buggy. He was truly one of Europe’s greatest swordsmen only suffering one defeat in his extraordinary fencing career. He graduated from the fencing boarding academy in 1766 earning the titles of Officer of the King’s Bodyguard and Chevalier (knight). Despite being the illegitimate son of a slave woman, Saint-George the “god of arms” was a well-respected fencer and horseback rider who’s future was about to shine brighter than he may have imagined. Music would be Saint-Georges new realm that he would soon conquer, the violin and the harpsichord (an early piano) would become his new weapons. It is believed Saint-George studied the violin with Jean-Marie Leclair-The Elder, a Baroque violinist, composer, and founder of the French violin school. It was revealed that Saint-George was a violinist when he performed two concertos composed for him by violinist Antonio Lolli, and a set of François Gossec’s six string trios, Op.9. Saint-George’s musical talents indicated that he studied with great teachers but there is not enough information available to validate who the teachers were. In 1769, Saint-George became a violinist for the Le Concert des Amateurs orchestra which was directed by François Gossec. Saint-George was so good that he was the first violinist and eventually became the director of the orchestra succeeding Gossec. He was somewhat of a legendary figure in France because of his success as a fencer and violinist. His first compositions, Op. 1 a set of six string quartets were among the first quartets to be played in France. Saint-George was successful but he was still a mulatto and considered by some a second-class citizen. King Louis XVI opposed the abolition of slavery, interracial marriages were illegal and black people in France were looking for a change. Racial ignorance would rear its ugly head as Saint-George was denied the opportunity to become the director of the Paris Opera in 1775. It is believed that two of the opera’s leading soprano’s felt insulted by the notion of being led by a mulatto. Saint-George would compose six opera’s and several songs in manuscript between 1771 and 1779 along with many other pieces of music and opera. There are claims that Saint-George was sometimes called the black Mozart and the black Don Juan because he was just as popular as Mozart. I do not have the information to confirm that he was considered the black Mozart, but we do know he was a musical legend. Race seemed to play a critical role in some of the most important or questionable situations Saint-George would face. In 1779, he and his friend were attacked by people believed to be policemen because of his relationship with Marie Antoinette. In 1781, Saint-George began composing and conducting music with his new group Concert de la Loge Olympique after the Concert des Amateurs stopped playing together. In 1787, he conducted one of six of the “Paris Symphonies” created by composer Franz Joseph Haydn. Saint-George’s ability to bounce back from adversity was uncanny; he wrote the opera’s The Girl-Boy and The Chestnut Seller, he also defeated the Chevalière d’Éon a French diplomat in a fencing exhibition. He would spend time in England supporting the blacks in their anti-slavery movement; his actions were deemed as inappropriate and troublesome by British slave dealers and owners. While in London five men would attack Saint-George in retaliation to his anti-slavery work but his swordsmanship once again allowed him to fight off the attackers. He would go on to continue his anti-slavery work as well as create a French anti-slavery group called the Society of the Friends of Black People. He would also become France’s first black Free Mason reaching the 33rd degree. Injuries and age did not slow Saint-George down a bit, during the French Revolution he became captain of the National Guard. As France and Austria engaged in war Saint-George became the colonel of an all-black French legion which was often called the “Saint-George” Legion. The Saint-George led legion helped the French defeat Austria, he and his legion also helped to stop a French general from conspiring with Austria to defeat France. Saint-George was publically condemned by Alexander Dumas, the father of the literary giant Alexander Dumas, due to Dumas’ allegiance to the revolutionary leader Robespierre. Saint-George spent a year in jail because of Robespierre but was released in 1794 because Robespierre was no longer in power. Saint-George witnessed the impact of French and Spanish colonization of the black people of the island of Santo Domingo; black people were fighting each other as enemies even though they are only separated by a river, languages and European ideas. His name as a composer was still drawing large crowds in France which led him to become the director of The Circle of Harmony orchestra. Saint-George would die in 1799 due to a bladder infection but was a legendary figure until the rise of Napoleon Bonaparte. The African presence of France was erased for over two-hundred years because of Napoleon and his racist views of African people. Like here in America, France had a rediscovering of African history, culture, and art which helped the people of France become reintroduced to this historical titan. Joseph Bologne, Chevalier de Saint-George, we proudly stand on your shoulders. J.A. Ward. References:

http://www.blackpast.org/gah/saint-georges-le-chevalier-de-joseph-de-bologne-1745-1799 http://www.notablebiographies.com/supp/Supplement-Mi-So/Chevalier-de-Saint-George-Joseph-Boulogne.html http://parkersymphony.org/the-black-mozart https://www.neh.gov/humanities/2010/mayjune/statement/black-mozart https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Chevalier_de_Saint-Georges

1 Comment

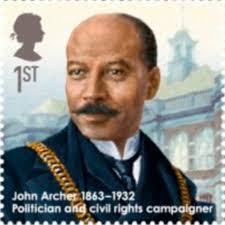

On February 26th, 1943 a baby boy named Leighton Rhett Radford Howe was born in Moruga District, Trinidad, to parents Cipriani and Lucille Howe. Early in Howe’s academic career he attended the Queen’s Royal College (QRC) on a scholarship. Upon graduating from the QRC he traveled to London, England to study law at The Honorable Society of the Middle Temple (Middle Temple), he attended Middle Temple for two years before developing an interest in the field of journalism and returning to Trinidad in 1969. While in Trinidad Howe was heavily influenced by his uncle C. L. R. James to use journalism and political activism as a tool for liberation. C.L.R. James was an Afro-Trinidadian historian, journalist, socialist and pioneering voice in postcolonial literature. Following his passion for journalism Howe worked as the assistant editor for the Vanguard, a Trinidadian newspaper owned by the Oilfields Workers’ Trade Union. Howe learned about a US based black empowerment organization called The Black Panthers whose message was spreading to black people around the globe. In 1970, Howe moved back to London, England and became involved with the British Black Panther Movement; this is also the time he gained the nickname “Darcus”. The summer of 1970 brought about Howe, The Black Panthers and Althea Jones-Lecointe organizing with their communities to protest the British police’s constant raids of a Caribbean restaurant called the Mangrove Restaurant. The Mangrove Restaurant was owned by Frank Crichlow a black entrepreneur and activist the British police labeled as an adversary. Howe was employed at the restaurant and the establishment was used as a citadel for black organization and empowerment; the restaurant was raided at least twelve times by the police. The community protested of the constant police raids of the restaurant, one protest grew into one hundred and fifty people descending upon the police stations to protect their community members. The protest was peaceful until the people were attacked by a large number of police officers leading to many injuries and arrest of the protesters. The trial of the Mangrove Nine was a high profile landmark trial which placed black empowerment for black Britain in opposition with the local police force and the legal system. The Mangrove Nine consisted of Barbara Beese, Rupert Boyce, Frank Critchlow, Rhodan Gordon, Darcus Howe, Anthony Innis, Althea Jones-LeCointe, Rothwell Kentish and Godfrey Millett. The Mangrove Nine were arrested and charged with inciting a riot during their protest even though they were attacked by the police. Howe commanded that the Mangrove Nine be given an all-black jury for the trial but his command was denied. In 1971, the Mangrove Nine were forced to endure a trial that lasted for fifty-five days ultimately ending in all nine people being acquitted of all charges. The judge presiding over the trial acknowledging that the police officers who opposed the protesters were motivated by racial hatred was a pivotal moment within the trial. Later the judge was forced to retract his statement of motivation by racial hatred; by the time of the retraction the impact of his original statement was greatly felt. In 1973, Franco Rosso, John La Rose and Horace Ové teamed with Howe to produce the documentary film The Mangrove Nine which provides background details of the protest and trial. Later in 1973, Howe served as editor of the Race Today magazine which was established in 1969 by a black think tank called the Institute of Race Relations. Under the control of Howe the Race Today magazine was moved to Brixton in South London and became known as a black radical newspaper because it focused on the issues that were concerning black Britain. Howe recruited black activist to write for the magazine such as Farrukh Dhondy, Linton Kwesi Johnson, Barbara Beese and Leila Hassan; Hassan eventually succeed Howe as the editor of the magazine in 1988. Howe would use the magazine as an instrument to help deliver messages to the masses and to bring political and community change. They supported the Asian female worker strike, as well as, helped to organize a community squat in that resulted in the community members gaining housing and benefits. In 1977, Howe was wrongfully arrested and sentenced three months in jail for an assault charge. The charge was appealed and protest broke out to clear the name of Darcus Howe. Eventually the charge was dropped and Howe was released from jail. Howe and the Race Today magazine took on their biggest story when they became involved with the New Cross house fire. During a house party in the New Cross district of London thirteen young blacks were killed in a house fire that was believed to be started by white racist. The mainstream media used its power to convince the masses that the fire was a result of carelessness by the teens and was not racially motivated. In retaliation to the media’s side of the story Howe and others used strategies that were learned from black political heroes in the US to organize black Britain’s largest demonstration on a Monday. Over two thousand people showed up to voice their frustrations with racism and the media that supports it. After the demonstration the British police responded by using systematic racist tactics and the stop and frisk terror was intensified against black Brits. The tension between black Britain and the police led to three days of violence called the Brixton Riots. Black people in Britain took their frustrations against the police to the streets and faced their oppressors head on. Howe and the Race Today magazine was able chronicle the ordeal and tell the story from the standpoint of the oppressed people. Howe’s journalism career led him to appearing on television starting 1982 with the television series Black on Black. Howe co-edited the series with a man named Tariq Ali; both Ali and Howe would collaborate on two other television series’ Bandung File and White Tribe. In 1992, Howe hosted a television show title The Devil’s Advocate for the local channel 4 British television. He also was a writer for The New Statesman, a British political and cultural magazine. In 2005, Howe was a keynote speaker and debuted his documentary film Who You Callin’ a Nigger? at the Belfast Film Festival’s “Film and Racism” seminar. Late in 2005, Howe produced another documentary titled Son of Mine about his uneasy relationship with his son. On April 1st, 2017, Darcus Howe died of prostate cancer at the age of seventy-four. He was married three times, produced seven children and left behind a legacy of activism, organization and empowerment. Howe was a brilliant man who knew how to get his community involved in its own liberation. He understood the power of the media and why he needed to have black people documenting and telling their own stories. If it wasn’t for him and the Race Today magazine team, many more stories that impacted black Britain would have gone unknown but still negatively affected the lives of the people. Mr. Leighton Rhett Radford “Darcus” Howe, we proudly stand on your shoulders. J.A. Ward John Richard Archer was born on June 8th, 1863 in Liverpool, England; his parents were Richard Archer and Mary Burns. Richard Archer was a black man from Barbados and Mary Burns was and Irish woman living in England. Archer was able to see the world when he joined the British Navy, as a seaman his travels would allow him to take up residence in the United States and Canada. While living in Canada Archer would meet and marry a black Canadian woman named Bertha. He also opened a small photography shop during the time when photography was only around roughly 60 years (Photography was introduced to the world in 1939). Archer gained an interest in the local politics of London by becoming acquainted with the social activists who were labeled “radicals”. This affiliation led Archer to being elected as the Progressive to the Battersea Borough Council for the Latchmere ward in 1906. As the progressive to Battersea, he successfully campaigned for a minimum wage of 32 shillings a week for the council workers. Unfortunately, he was not reelected as the progressive until 1909, but his campaign in 1912 allowed him to once again be elected as the Progressive for Battersea. In 1913, Archer was nominated and won the election for the seat as the mayor of Battersea, London. Archer was the first black mayor in London’s history, but the second black British Mayor. Archer quoted the following during his victory speech: “My election tonight means a new era. You have made history tonight. For the first time in the history of the English nation a man of color has been elected as mayor of an English borough. “That will go forth to the colored nations of the world and they will look to Battersea and say Battersea has done many things in the past, but the greatest thing it has done has been to show that it has no racial prejudice and that it recognizes a man for the work he has done.” In 1919, he was re-elected to the Battersea Counsel but he was representing the Labor Party, which was a broad church bringing together an alliance of social-democratic, socialist and trade-unionist outlooks. He would become the president of the African Progress Union in 1918, a union that worked for black equality and empowerment in London. In 1919, he served as a British delegate to the Pan-African Congress in Paris, France; he would follow this event with his own Pan-African Congress in London two years later. In 1922, Archer would step down from his position as progressive of the Battersea Borough Council to help Shapurji Saklatvala campaign for the position. He used his influence to convince the Labor Party to endorse Saklatvala while he became one the first black members of parliament in London’s history. Saklatvala was a communist activist standing for parliament in North Battersea before collaborating with Archer, he became the Progressive for Battersea in 1922 and 1924 with the help of Archer. The Labor Party would eventually split shortly after 1924; Archer would become the agent for the person who defeated Saklatvala in the 1929 election for the Progressive of Battersea. Later in his life Archer would become the governor of the Battersea Polytechnic Institute, which is now The University of Surrey, a public research university located in Guildford, Surrey, in the South East of England, United Kingdom. He would also become the President of the Nine Elms Swimming Club, Chair of the Whitley Council Staff Committee, and a member of the Wandsworth Board of Guardians. In 1931, he was reelected for the Nine Elms Award just before his death in July of 1932. During the time of his death he was the deputy leader of the Battersea counsel. Archer was following in the footsteps of Mr. Allen Glaisyer Minns, the first black British mayor. Archer used his platforms to help fight for justice and equality for the black people of London. He believed in challenging the system to get results that helped change the conditions of his people. Black British history is not taught at all within our school systems or any other historical medium, it is a great tragedy because we are unaware of the struggles and accomplishments of our people across the pond. The story of Archer is an example of black excellence in Europe, as well as, a reminder of how much more we have to learn about our history. Mr. John Richard Archer, we proudly stand on your shoulders. J.A. Ward Olive Morris was born to parents Vincent and Doris Morris in St. Catherine, Jamaica in 1952. The Morris family moved to London, England in 1961 where she would leave a legacy her community would never forget. It is said the Morris did not complete grade school but she did go on to earn her doctoral degree in social science from Manchester University. As a teen living in South London Morris became active within the political movements that were gaining momentum in London. In her adult years she was a founding member of several groups who fought for the rights of blacks, women and “squatters.” (Squatters were the less fortunate people of London who usually in abandoned buildings.) The Organization of Women of African and Asian Descent, the Brixton Black Women’s Group, the Manchester Black Women’s Co-operative, the Manchester Black Women’s Mutual Aid Group, and the Brixton Law Center are the organizations Morris help to found. She was an active and visible ally to the squatter’s movement as well as a member of the Black Panther Party during the 1970’s. At the age of 27 Morris unfortunately died of non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma, but her spirit and influence did not leave the people of South London. Morris’ contributions were not overlooked by her community, the Lambeth Council, a local authority for the Borough of Lambeth in Greater London, honored her by naming one of its council buildings after her. The people of London voted to have Morris depicted on the one pond note of the local currency in Brixton, London. To call Olive Morris a brave woman would be an understatement; in 1969 she witnessed a Nigerian Diplomat being arrested because the police thought his Mercedes was too fancy for him. As the police began to beat the man, Morris broke through a crowd to come to the man’s aide. She was threw to the ground by the police, kicked and stomped in the breast, and finally stripped naked by the police as they told her; “This is the right color for your body,” referring to the bruises upon her body. Despite facing constant racism, threats and attacks, she continued to fight for the rights of black people, women and the poor people of London. She was determined to exhaust her energy and resources to make sure her people would no longer be oppressed. Olive Morris, we proudly stand on your Shoulders. References:

http://www.brixtonbuzz.com/2016/06/brixton-community-activist-olive-morris-remembered-as-squatters-leave-gresham-road-premises/ http://news.bbc.co.uk/local/london/hi/people_and_places/history/newsid_8310000/8310579.stm https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Olive_Morris https://rememberolivemorris.wordpress.com/contribute/ http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/00064246.2016.1147937?scroll=top&needAccess=true&journalCode=rtbs20 Benjamin Obadiah Iqbal Zephaniah was born in Birmingham, England in 1958. He was raised in the Handsworth district of Birmingham, which is considered the “Jamaican district of Europe.” At the age of 13, Zephaniah stopped attending school because he felt it was neither inspiring nor beneficial to him as an aspiring poet. Zephaniah states that his poetry was heavily influenced by a brand of Jamaican music and poetry called “Street Politics.” He performed for the first time as a ten year old in him hometown Church. By the time he was fifteen he was a well-known teen poet in his hometown. He marveled many people because of his knowledge of local and international affairs, and his excellent ability to communicate his thoughts. As Zephaniah’s reputation grew he began to gain a flowing within the African-Caribbean and Asian communities. He also began to grow frustrated speaking out about injustices against black people in Europe. He felt that his message would have a more powerful affect if he performed in front of larger more diverse audiences. Zephaniah moved to London at the age of twenty-two where he published his first book, Pen Rhythm. His book was published by Page One Books which was an East London based publishing company. Page One Books was in support of Zephaniah’s poetry and the new movement happening in London. The book was fairly successful and it helped Zephaniah to start a poetic revolution. He is considered a “Dub Reggae Poet,” his style of poetry helped to revitalize the poetry scene in London, it also caught the attention of the mainstream media. It was a sweet victory for Zephaniah; many of the publishers who were seeking him out rejected his work in the past. When the youth of London swarmed the streets in the 1990’s protesting against inequality and injustice, Zephaniah’s influence was felt throughout the protest. The spirit of justice and freedom penetrated every aspect of the culture of London’s youth. Zephaniah became London’s most recognized poet, his ability to perform on stage and on the television made him a household name. His mission was to make poetry popular, popular enough that any youth who did not read, would develop a love for poetry and reading. Zephaniah was known for transforming his poetry into live events every time he performed. Zephaniah became very important by using his platform to bring attention to the issues that affected his people. During the 1990’s Zephaniah’s popularity increased as he was constantly in the public’s eye. His books, music and television appearances increased and his demand grew. He believes that the oral tradition of Africa never dies in the artist. In 1991 he held a performance on every continent within a 22 day period. In 1982 Zephaniah was the first artist to perform with the Wailers after the death of Bob Marley. The song was a tribute to Nelson Mandela on Zephaniah’s Rasta LP. Mandela was able to hear the song while imprisoned, once released he requested a meeting with Zephaniah. The two build a relationship that allowed Zephaniah to teach the children of South Africa. In 1996, Zephaniah also hosted Mandela’s Two Nation’s Concert held at Royal Albert Hall. His next step was to release a children’s book of poetry titled Talking Turkeys. The book was so popular that it needed an emergency reprint to meet the demands. Talking Turkeys topped the bestselling children’s book list for three weeks. In 1999 Zephaniah wrote a book for teen’s titled Face, which was the first of four novels in a series. He is an honorary patron of The Vegan Society and often advocates for the rights of animals. From 1998 to 2008 Zephaniah received honorary doctorate degrees from, The University of North London, The University of Central England, Staffordshire University, London South Bank University, The University of Exeter, The University of Westminster, and The University of Birmingham. He was considered number 48 on Time Magazine’s list of 50 Greatest Postwar writers. Dr. Benjamin Zephaniah, we proudly stand on your shoulders. J.A. Ward. Alessandro de Medici was born in Florence, Italy in 1510 to a mother who was a servant girl. His mother served the de Medici family, his father was said to be Pope Clement VII, the nephew of Lorenzo de Medici “The Magnificent.” Alessandro was nicknamed the “Moor” by his peers because of his prominent African features. He was appointed regent of Florence in 1523 after Pope Clement was forced to relinquish his power. Clement assigned Alessandro as regent to maintain his influence. In 1527 Emperor Charles VII sacked Rome forcing Alessandro and members of his family to flee for safety. The city remained under siege until 1530 when Pope Clement mended his relationship with Emperor Charles. The emperor used his military power to restore the Medici family as heads of state. The emperor also used his power to appoint Alessandro as Duke of Florence. He began his reign in 1531 and within six months was made hereditary duke by the emperor. This move helped the Medici’s overthrow the opposing republican government. The Duke’s reign was not received very well by his enemies and those exiled by Emperor Charles. Alessandro and his supporters were viewed as oppressive and incompetent by those that despised there position. The people of Florence didn’t agree with the many actions of the Duke. His cousin Ippolito was sent to appeal his reign to Emperor Charles. Upon his journey Ippolito was killed and Alessandro was suspected of orchestrating his death. Pope Clement died in 1534 creating an opportunity for Alessandro’s enemies to attack him. In 1536 he married Emperor Charles’ daughter to help cement Alessandro as the absolute Prince of Florence. Months after Alessandro’s marriage, he was assassinated by his cousin Lorenzo De Medici. They lured him into bed with another woman, assassinated him, and quietly moved his body to a designated burial ground. Emperor Charles held a small funeral in the memory of Alessandro in his courts. Lorenzo later fled to Venice where he was killed by supporters of the Medici family. The family remained in power by ensuring Cosimo De Medici became Duke of Florence. Alessandro and his family was an example of the African diaspora in Europe, rising to prominence. The family was able to survive the sacking of Rome by Emperor Charles, and the uprising of a Republican government to remain the rulers of Florence. Alessandro was not well liked or highly thought of by his enemies, but he was effective in helping to maintain his family’s power. Alessandro de Medici, we stand on your shoulders. J.A. Ward. Click below to view the Alessandro de Medici video. |

Details

Categories

All

Click Here to join our mailing list

|

Contact Us: |

Connect With Us |

Site powered by PIT Web Design

RSS Feed

RSS Feed