|

In November of 1854, Reverend Byrd Parker and his wife Jane Janette Johnson welcomed a baby girl named Lillian Parker Thomas while living in Chicago, Illinois. Reverend Parker was the head Pastor of Quinn African Methodist Episcopal Church, and Jane Thomas was a teacher. Reverend Parker moved his family to Oshkosh, Wisconsin when Lillian was a young girl, they also moved to Indianapolis, Indiana. Reverend Parker died in 1860 while living in Oshkosh, Wisconsin. Years later, Jane would marry a man named Robert E. Thomas, they would produce two children. Lillian began reading and writing at a very young age, this would benefit her as her family eventually moved to Indianapolis. She learned how to sew and became a freelance writer for newspapers to earn money for her family. Academically, she earned an education from the Indiana-Boston School of Elocution and the Indianapolis Institute for Young Ladies. Over the years, Lillian mastered her writing skills and by the age of 26 she became a reporter and correspondence editor for the Indianapolis Freeman, a well-known nationally distributed black-owned newspaper. She also gained a reputation as an excellent public speaker touring throughout the Midwest and the South several times representing various organizations. In 1872, Lillian married a man named Wm. R. James, and the couple produced a daughter. The couple was married for 8 years before divorcing. In 1881, Lillian married Charles M. Thomas, they were married for 8 years, they divorced shortly after moving to Indianapolis, Indiana. Later in 1889, Lillian’s daughter would pass away. Lillian continued to build upon her career as a writer and a public speaker. In 1893, she married James E. Fox in Indianapolis, they were married for 5 years due to James Fox passing away in 1898. During her marriage to James Fox, Lillian retired from her job with the Indianapolis Freeman, but did continue her public speaking tours and writings from home. After the passing of Fox, she began writing for the Indianapolis News in 1900. This move made her the first African American to write a weekly column for the newspaper. In addition to writing and speaking, Lillian was active in her community. She joined several organizations aimed at improving, empowering, and protecting black communities in Indianapolis. She co-founded the Women's Improvement Club in 1903. In 1904, she was in charge of the organization that provided funding for the Indiana State Federation of Colored Women's Clubs. She also helped to advocate for their local health centers to treat black patients with tuberculosis. Lillian used her writings to empower her people and was compared to Booker T. Washington. For 15 years, she wrote the column “News Of The Colored Folk” for the Indianapolis News and used her platform to promote local organizations, successes, progress, and the beauty of her community. As a speaker, she used her voice to amplify the messages in her writings. She became an Indiana state representative for the National Afro-American Council’s executive committee. She also became a representative for the Indianapolis Anti-Lynching League, and the National Association of Colored Women's Clubs. In 1895, Lillian was a guest speaker at the Atlanta Congress For Colored Women. As she aged she continued to write, speak, and collaborate with black organizations to uplift black Americans. As her health began to fail, she retired from the Indianapolis News in 1915. In August of 1917, Lillian Parker Thomas Fox died as a black pioneer in the state of Indiana. She opened the door for other black writers to not only write for black and white news papers, but to create their own lanes to write, and use their voices and their writings to make a living and make a difference. To Mrs. Lillian Parker Thomas Fox, we proudly stand on your shoulders. J.A. Ward Click here to support the OTSOG book series. References: https://search.alexanderstreet.com/view/work/bibliographic_entity%7Cbibliographic_details%7C3957496/biographical-sketch-lillian-parker-thomas-fox https://indyencyclopedia.org/lillian-thomas-fox/ https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lillian_Thomas_Fox

0 Comments

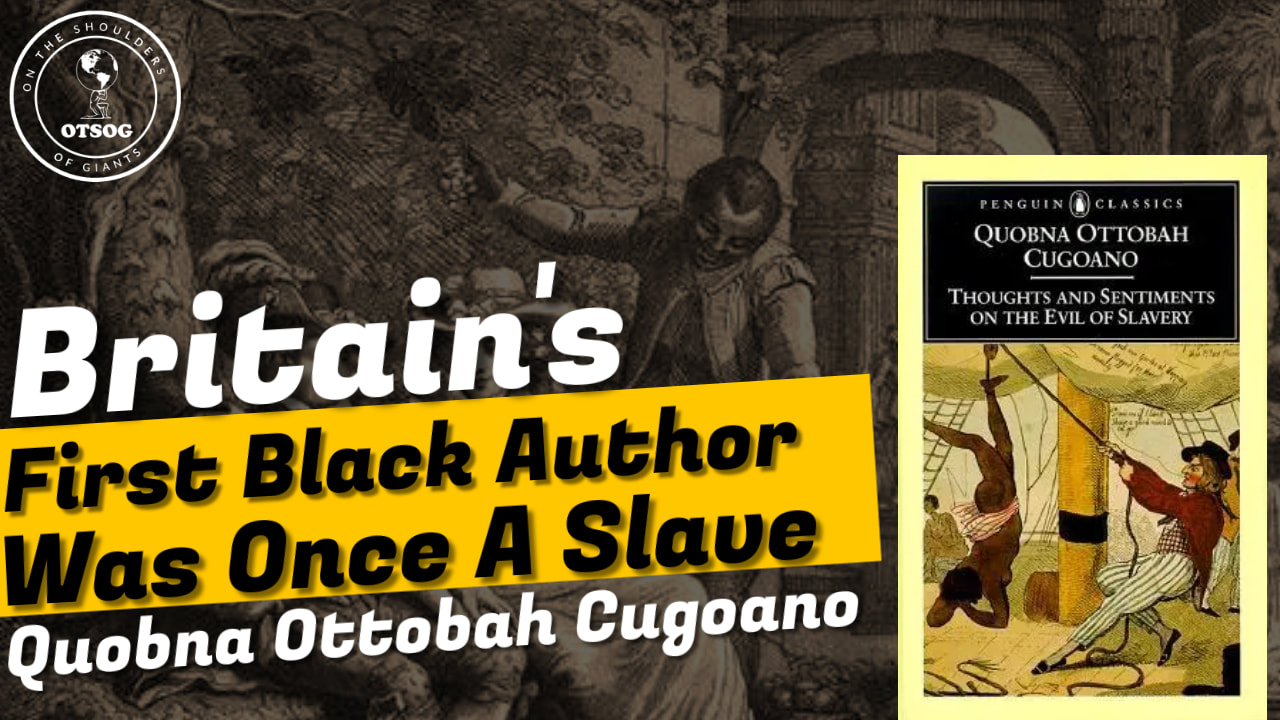

We begin our story in the village of Ajumako located on the coast of present-day Ghana. Quobna Ottobah Cugoano was said to be born around the year 1757, not much is known of his early life. At the age of 13, Ottobah was kidnapped and sold to slave traders, along with a number of other boys and girls while playing in a field. Ottobah spoke about him and other children attempting to escape but were unable because guns were used to threaten their lives. The Europeans shipped Ottobah and other captives to the island of Grenada to work on a plantation. For two years, he worked plantations in Grenada and other islands of the Lesser Antilles. In 1772, Ottobah was sold to a well-known slave owner named Alexander Campbell and shipped to London, England. Campbell baptized Ottobah in 1773 and changed his name to John Stuart. It seemed to be a strategy behind Ottobah being baptized and converting to Christianity. Becoming a Christian helped him not only escape being sold again, but he eventually gained his freedom. I do not know exactly how he gained his freedom, but it is believed that his conversion to Christianity helped him gain his freedom. Because of a previous court ruling known as the Summerset Case, it became unlawful for a freedman to be sold back into slavery. As a free black man living in London, Ottobah dedicated himself to learning to read and write, skills he would use to advocate for his people. In 1784, Ottobah began working at the Schomberg House as a servant for Richard and Maria Cosway. During this time he began using his voice and his writings to campaign against the practice of slavery. Ottobah’s activism along with two other men helped to prevent a man named Harry Demane from being enslaved on an island in the Caribbean. Ottobah was making a name for himself as an advocate and activist against the enslavement of African people. He wrote several letters speaking out against slavery to the various London newspapers and influential men in London. In 1787, the once enslaved man published his first book titled, Thoughts and Sentiments on the Evil and Wicked Traffic of the Slavery and Commerce of the Human Species, Humbly Submitted to the Inhabitants of Great Britain. Ottobah wrote about his experience and the experience of other enslaved people to illustrate the horrors of slavery. His goal for the book was to inspire the abolition of slavery. Ottobah is known as the first black British author. His book is also considered a classic book and one of the greatest books of its era. While working and living at the Schomgerg House, Ottobah was exposed to prominent members of society, he was even exposed to British royalty. The Cosways would host popular parties that were attended by people such as Edmund Burke and the Prince of Wales. The Prince of Wales is one person Ottobah would often write to condemning slavery. It is believed that the Prince of Wales read the second edition of Ottobah’s book. In 1791, Ottobah wrote a letter describing how he will be traveling to promote his book. This letter was the last time anyone heard or saw anything from Ottobah. Many believe he may have died in 1791. A young boy was taken from his family and land, shipped to the Caribbean, then to London, was converted to Christianity, gained his freedom, then spent the rest of his life fighting to free African people from slavery. To Ottobah Cugoano, we proudly stand on your shoulders. J.A. Ward Click here to support the OTSOG book series. References: https://www.english-heritage.org.uk/visit/blue-plaques/ottobah-cugoano/ https://aaregistry.org/story/ottobah-cugoano-born/ https://www.blackhistorymonth.org.uk/article/section/bhm-firsts/ottobah-cugoano/ On July, 15 1864, Maggie Lena Draper was born in Richmond, Virginia, on the Van Lew estate, in the St. John’s Church Historic District. Walker’s parents were Elizabeth Draper and Eccles Cuthbert. Walker’s mother, Elizabeth Draper was a formerly enslaved woman who worked as an assistant cook for Elizabeth Van Lew. Her father Eccles Cuthbert was a reporter for the New York Herald newspaper living in Virginia. Draper and Cuthbert met on the Van Lew estate. They never married and only produced one child together, according to my sources. Shortly after Walker was born, her mother married a man named William Mitchell who worked on the Van Lew estate as a butler. In 1870, William Mitchell and Elizabeth Draper produced a son, Johnny Mitchell. William Mitchell received a job as the head waiter at the Saint Charles Hotel, one of the most distinguished hotels in Richmond. William was able to move his family off of the Van Lew estate and into a small house near the Medical College of Virginia. Tragedy struck the Mitchell household in February of 1867. William Mitchell’s body was found floating in a river. His death was ruled self-inflicted, but Elizabeth Mitchell believed very strongly that her husband was killed. Following the death of William Mitchell, Elizabeth struggled to provide for her two children and her family was forced into poverty. To provide for her family, Elizabeth started a laundry business washing and drying clothes for white families. Walker would often help her mother by returning the clean and dried clothes to their owners. While transporting the cleaned clothes, Walker noticed a stark difference in the quality of living between blacks and whites. “I was not born with a silver spoon in my mouth, but with a laundry basket practically on my head”, is a quote from Maggie Walker. A quote that explains her childhood. A time in her life that left a lasting impression, and inspired her to become a highly-successful woman. Walker received an education that can be thought of as privileged, despite living in poverty. She attend the newly formed Richmond Public Schools that were founded for black people and children to learn. She was in the number of black children who were able to attend school. Walker attended the Lancasterian School, the Navy Hill School, and the Richmond Colored Normal School. She graduated from the Richmond Colored Normal School in 1883, where she was trained to be a teacher. For three years, Walker taught at the Lancasterian School to make a living for herself. Walker met a man named Armstead Walker Jr., the two became a couple, then were married on September 14, 1886. Armstead worked as a construction worker while Maggie Walker worked as a teacher, until she was forced to quit her job. The Lancasterian School had a policy that married women could not teach. Maggie and Armstead produced three sons and adopted a daughter. The Walker’s were able to purchase a home for their family in Richmond’s Jackson Ward neighborhood, which was thought of as the “Harlem of the South”. Before graduating from the Richmond Colored Normal School, Walker became a member of The Independent Order of St. Luke, which was a subgroup of The United Order of St. Luke, an organization that focused on providing resources and care for the sick and dying. At the time, the previously mentioned sororities were dedicated to helping black Americans advance in society. Walker, believed in focusing on our children and raising them up with the proper tools and education to be productive black citizens. Walker became the Grand Secretary of the Independent Order of St. Luke after the organization voted to replace William M.T. Forrester, because the organization was going bankrupt. Maggie Walker was a dedicated and focused leader. When she became Deputy Secretary of The Order it was in debt, but not only did she pull the organization out of debt, but she was able to raise over $3.5 million dollars during her tenure. She also expanded the organization by 100,000 members. In August of 1901, Walker gave a speech that would become iconic. She addressed The Order and gave her plans to expand The Order, but also uplift her community by founding a bank, newspaper, and department store. All owned and operated by black people. Within five years of giving her plans, Walker led her community to establishing their bank, newspaper, and department store. Self-sufficiency was Walker’s goal for her people. The St. Luke Herald was established in 1902, the St. Luke Penny Savings Bank in 1903, and the St. Luke Emporium in 1905. The establishing of these businesses made a huge impact on the economics of black Richmond. Black people were able to not only provide the necessities for their families, they also built enough wealth to create a middle class. To help The St. Luke Penny Savings Bank survive the Great Depression, Walker merged the bank with two other banks creating the Consolidated Bank and Trust Company. Walker often faced challenges because of operating a successful black owned business in the Southern United States in the early 1900s. A white fraternity attempted to start a bank similar to what Walker was able to do. The white fraternity failed, as a result, a new mandate was enacted, from then on fraternal organizations and banks had to be separate entities. Because Walker’s vision was working so well, the bank was able to be separated from The Order because of the support of the members, also the department store and the newspaper was still successful. The St. Luke Emporium was forced to close down in 1911 because white business owners were jealous of Walker’s successful plans. Black people in Richmond were terrorized and threatened if they continued to patronize the St. Luke Emporium. Tragedy struck the Walker family in 1915, Maggie and Armstead’s son Russell Walker mistakenly shot and killed Armstead because he thought he was breaking into their home. Russell was tried but found not guilty of murder. That event negatively affected Russell’s mental health until his death in 1923. Maggie Walker was diagnosed with diabetes and later bound to a wheelchair because her health was continuing to fail her. Despite her health, Walker remained a force for change in black America. She continued to advocate for and assist in the advancement of black people in America. She co-founded the Richmond chapter of the NAACP and Council of Colored Women. She helped organize a bus boycott in 1904 that caused a Richmond bus company to go out of business. In 1921, Walker tried her hand at politics, as one of the candidates running on what was called the “lilly black republican ticket”. Walker was running for superintendent of public instruction but did not win the election. On December 15, 1934, Maggie Lena Walker died. She left behind a legacy that black people today can be proud of. She didn’t just talk about uplifting her community, she literally did it. Creating a bank, newspaper, and department store for her people to operate and patronize, that brought money into their community, helping their community to thrive, is exactly the example we need to change our situation. To the brilliant and brave leader, who literally lifted her people out of poverty, Mrs. Maggie Lena Walker, we proudly stand on your shoulders. J.A. Ward Click here to support the OTSOG book series. References: https://encyclopediavirginia.org/entries/walker-maggie-lena-1864-1934/ https://www.biography.com/scholar/maggie-lena-walker https://americanhistory.si.edu/blog/maggie-walker https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Maggie_L._Walker |

Details

Categories

All

Click Here to join our mailing list

|

Contact Us: |

Connect With Us |

Site powered by PIT Web Design

RSS Feed

RSS Feed