|

The blues is one of America’s oldest, most prominent, and alluring forms of music. The blues was created by black Americans who were formerly enslaved, but still lived in oppressive conditions. It was a form of musical expression that portrayed the raw emotions black Americans expressed, because of the conditions they lived in. Charley Patton was born in April of 1891, in Hinds County, Mississippi, but was raised in Sunflower County, Mississippi, within the Mississippi Delta. Bill and Annie Patton were Charley’s parents; though many believed that Patton’s father was a man named Henderson Chatman, a formerly enslaved black man who fathered many musicians. Charley Patton was 5’5 tall, fair-skinned, and believed to be of black American and Native American ancestry. Stories exist about Patton being of Cherokee or Choctaw tribes, the Cherokee claim is believed because Patton made the song “Down in the Dirt Road Blues” about visiting the Cherokee tribe. 1897 was the year the Patton family moved from Sunflower County, Mississippi to the Dockery Plantation in Ruleville, Mississippi. Moving to Ruleville, Mississippi would prove to be a pivotal decision in Patton’s life. Henry Sloan is the name of a legendary Mississippi Delta musician and the man that influenced Charley Patton’s style of music. Henry Sloan created the foundation for what we know as Mississippi Delta Blues. Patton learned a lot about music and Mississippi Delta Blues from Sloan, soon after, Patton was making a name for himself within the Mississippi Delta. He quickly became one of the most talented and popular blues artists in the delta. He would travel from plantation to plantation performing and gaining notoriety. We would begin to forge friendships with fellow delta blues legends such as Howlin’ Wolf, Willie Brown, Fiddlin’ Joe Martin, Tommy Johnson, and Robert Johnson. Because he was older than these musicians he would become a mentor to them. Patton’s talent and popularity grew to where he was invited to perform all over the South, New York, Chicago, and throughout the United States. His performance schedule was unusual at the time for a delta blues player because he had consistent scheduled performances. A performance schedule that others would soon adopt. Patton was a very talented musician, not only was he a master at playing Mississippi Delta Blues, but he could also masterfully play various genres of music including ballads and what was considered “hillbilly songs”. Showmanship is an attribute that was used to describe Patton as a performer. While playing the guitar, Patton would dramatically drop to his knees, then swing the guitar behind his head and back, continuing to play effortlessly, as the crowds roared in amazement. Many believe Patton created the foundation for Rock & Roll. Patton’s influence could be heard and seen in the way the delta musicians and musicians of other genres played their chords and their stage presence, some mimicking Patton’s dance moves and guitar swinging. Patton’s voice was very influential as well. It is said that Patton's voice could be heard from 500 yards away with no microphone. A number of people believe he influenced the way Howlin’ Wolf used his voice. In 1933, Patton and his common-law wife Bertha Lee moved to Holly Ridge, Mississippi. Their relationship was not healthy, they were combative with each other, which resulted in them being incarcerated. Patton’s career was not as long and successful as it should have been, due to the way black artists were exploited during the early 1900s. His final recording session was from January through February of 1934. He would die on April 28th, 1934 of a heart condition. Patton’s death was not reported by any news outlets, and his legacy was all but forgotten until his music and legacy were rediscovered. But his influence was already imprinted on the music industry. Considered the “father of the Delta Blues”, Charley Patton was responsible for contributing to over 54 music recordings between 1929 and 1934. Patton’s Screamin' and Hollerin' the Blues: The Worlds of Charley Patton was packaged and rereleased to the public in 2001, winning 3 Grammy awards in 2003. In 2006, Patton’s song “Pony Blues” was added to the National Recording Preservation Board of the Library of Congress. The documentary American Epic was released in 2017, depicting Patton's life. He was inducted into the Blues Hall of Fame in 2006, and the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 2021. This is the story of Mr. Charley Patton, the world of music stands on your shoulders. J.A. Ward Click here to support the OTSOG book series. References: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Charley_Patton https://www.elijahwald.com/patton.html https://aaregistry.org/story/charlie-patton-born/ https://www.blackpast.org/african-american-history/patton-charley-1891-1934/ https://www.elijahwald.com/patton.html

1 Comment

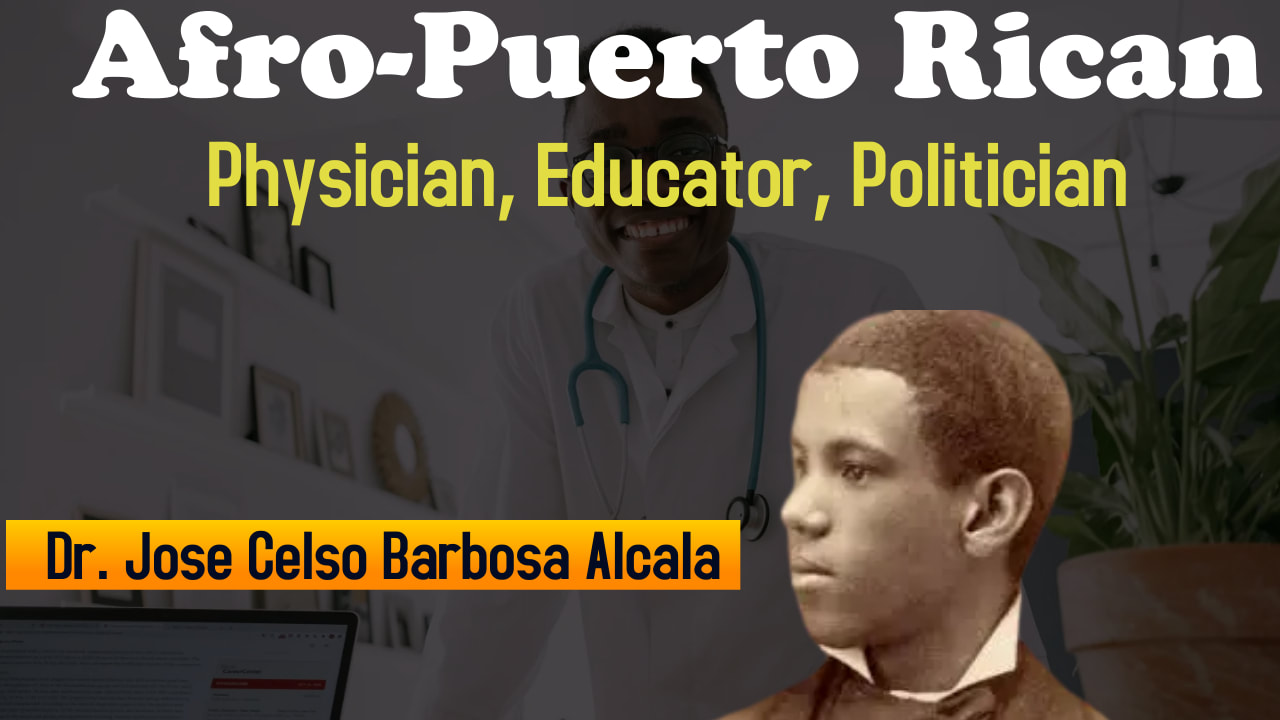

On December 18, 1912, Benjamin O. Davis, Jr. was born in Washington, D.C. His father was Benjamin O. Davis, Sr., a U.S. Army brigadier general who served 41 years in the military. Benjamin Jr’s mother was named Elnora Dickerson Davis. Not much information is available about her life. She was a mother and a wife who died in 1916 after giving birth to her third child. Benjamin Davis, Sr. taught his son about racism and to not allow anyone or anything to prevent him from being successful. Benjamin Davis, Jr’s interest to become a piolet was piqued at the age of 13 being able to fly along with a barnstorming piolet in Washington, D.C., from then on he was focused on becoming a pilot. In 1929, Davis graduated from high school in Cleveland, Ohio during the Great Depression, after graduating from Central High School, he began attending Western Reserve University, a research university in Cleveland. He would soon leave Western Reserve and attend the University of France and the University of Chicago, before attending the United States Military Academy at West Point in 1932. Racism, discrimination, and isolation are three words to describe what Davis experienced while attending West Point. His white classmates refused to speak to him, refused to become his roommate, and refused to offer any help to a fellow academy member. Davis was completely on his own as a cadet. His white academy members only talked to him in the line of duty. Despite the discriminations Davis faced, he graduated from West Point in 1936 35th in a class of 276 cadets. He was the first black man to graduate from West Point since 1889 and the fourth black man overall to graduate from West Point following in the footsteps of Henry Ossian Flipper, John Hanks Alexander, and Charles Young. Davis’ white classmates attempted to run him out of the academy, but he persevered and graduated as one of the best cadets in his class, he also gained the respect of his classmates. Davis applied for the U.S. Army Air Corps in 1934 but was denied because they did not accept black men. Davis was commissioned to become a second lieutenant. At the time, Benjamin Davis, Jr., along with his father Benjamin Davis, Sr., were the only two black Army officers who were not chaplains. Davis, Jr. married Agatha Scott in 1936 shortly after graduating from West Point. Later in 1936, Davis was assigned to the 24th Infantry Regiment in Fort Benning, Georgia, one of the original all-black buffalo soldier regiments. Neither Davis, nor his fellow soldiers were allowed to enter the base officer’s club because they were black. Davis began attending Fort Benning’s U.S. Army Infantry School in 1937, he was then assigned the Tuskegee Institute to teach military tactics, a position his father held at Tuskegee. Franklin D. Roosevelt ordered the U.S. War Department to create an all-black flying unit in response to demands for more black men in the military. 1941 was the year the first class of cadets entered their training at the Tuskegee Army Air Field, Benjamin O. Davis, Jr., was one of the initial cadets to enter and graduate class 42-C-SE from the Tuskegee Army Air Field in 1942. Davis graduated from aviation cadet training with Captain George S. Roberts, 2nd Lt. Charles DeBow Jr., 2nd Lt. Mac Ross, and 2nd Lt. Lemuel R. Custis. These were the first four black men to become combat fighter piolets in U.S. military history. Later in 1942, Davis was promoted to lieutenant colonel, he also became the commander of the 99th Pursuit Squadron, the U.S. Military’s first all-black pilot unit. In 1943, Davis’ unit was sent to Tunisia as one of their first missions. The Tuskegee Airman were also involved in a dive-bombing mission against the Germans during Operation Corkscrew, and supported the Allied forces invading Sicily. Davis was instructed to become the commander of the 332nd fighter group, an exceptional all-black air pilot unit. Shortly after Davis began leading his new unit, white senior officers were trying to stop Davis and his unit from being deployed into combat. Davis and his unit were said to be underperforming by their white counterparts. Davis did not sit and allow his men to be insulted and dismissed. Davis was angered by the proposals to dismiss his units, so he held a press conference at the Pentagon presenting all the facts of successes his units were having. The American Army General at the time George Marshall did not dismiss the Tuskegee Airman, but he did hold a review of their performance. The results of the review showed that the Tuskegee Airmen were performing at the same level or better than their white counterparts. In January of 1944, The Tuskegee Airmen were able to defeat 12 German piolets during combat while protecting the Anzio beachhead. Davis led the “Red Tails”, a nick-name given to the Tuskegee Airmen; a four-squadron group on many successful missions penetrating deep into German territory. As time passed, Davis became the commander of more and more all-black air units. One reason was because Davis was an excellent leader, another was no whites wanted to be lead by a black man. Out of the many missions led by Davis, the Tuskegee Airmen were able to shoot down 112 planes, and disabled around 273 planes on the ground, and only losing 66 total planes during the 15,000 missions. Davis personally embarked upon 67 missions flying various fighter planes and receiving awards for his performances such as the United States Silver Star Medal, and the Distinguished Flying Cross award. In 1948, President Harry S. Truman signed the executive order to end racial discrimination within the military. Davis was one of the military officers to help draft the integration order, helping the Air Force become the first branch of the U.S. Military to become fully integrated. After graduating from Air War College, Davis began working at the Pentagon and abroad for a twenty year period. During those twenty years he helped to develop the Air Force’s Thunderbird flight demonstration team. In 1953, Davis became commander of the 51st Fighter-Interceptor Wing in the Korean War. He became the vice-commander of the Thirteenth Air Force and commander of the Air Task Force 13, and temporarily promoted to brigadier general. In 1957, Davis became the chief of staff of the Twelfth Air Force, U.S. Air Forces in Europe in Western Germany. He was again temporarily promoted to major general in 1959 before permanently becoming the brigadier general in 1960. In 1961, he became the director of manpower and organization, and became the deputy chief of staff for programs and requirements. In 1962, he was permanently promoted to major general, and in 1965 he became the assistant deputy chief of staff, programs and requirements. Later in 1965, Davis was again promoted to chief of staff for the United Nations Command and U.S. Forces in Korea. Benjamin Davis, Jr. retired from the military in 1970. In 1998, Davis was promoted to general, U.S. Air Force (retired) by President Bill Clinton. Davis began as a 2nd lieutenant in 1936 and ended as a Four Star General in the U.S. Military. He died on March 10, 2002, but left an honorable legacy and broad shoulders for the next generations to stand upon. To General Benjamin O. Davis, Jr., we proudly stand on your shoulders. J.A. Ward Click here to support the OTSOG book series. References: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Benjamin_O._Davis_Jr. https://www.af.mil/About-Us/Biographies/Display/Article/107298/general-benjamin-oliver-davis-jr/ https://www.military.com/history/gen-benjamin-o-davis-jr.html https://aaregistry.org/story/military-pioneer-benjamin-o-davis-jr/ January 4, 1867, is said to be the birth date of Elizabeth Carter, a black woman whose mother was enslaved by a U.S. President. New Bedford, Massachusetts is Elizabeth’s birthplace. Martha Webb was the name of her mother, and former U.S. President John Tyler was the man who owned Martha Webb. Webb became a well-known abolitionist and conductor of the Underground Rail Road. Her passion for helping black people gain their freedom was inherited by Elizabeth Carter and would help to shape her future. Elizabeth developed an interest in architecture while attending New Bedford High School and the Swain Free School in New Bedford, Massachusetts. She not only created an interest, but she began developing her skills to become a future black architect. In addition to developing her skills in architecture, she attended the Harrington Normal School for teachers and earned a teaching certificate after becoming the first black person to graduate from the Harrington Normal School. Around the year 1890, Elizabeth began her teaching career at the Howard Colored Orphan Asylum in Brooklyn, New York, an orphanage founded by black Americans. In 1895, she began her work with the National Association of Colored Women's Clubs (NACWC). She became the secretary of the organization's convention in 1896. From 1906 to 1908, Elizabeth served as the vice-president of the National Association of Colored Women’s Clubs. 1901, was the year that Elizabeth began teaching at New Bedford’s Taylor School, making her the first black person to teach in New Bedford. In 1908, she became the president of the National Association of Colored Women’s Clubs after serving as the vice-president. She served as president until 1912. This is around the time when Elizabeth learned about the NAACP and decided to found her own chapter of the NAACP in New Bedford, Massachusetts. She later became a founder of the New England Federation of Women’s Clubs. She would serve as the president of the New England Federation of Women’s Clubs for over 27 years. As the president, she worked to make sure community organizations and organizations in need received the necessary resources to operate. She helped community centers receive funding, helped support scholarship funds, and supported the building of daycare centers in communities in need. In 1918, Elizabeth was recruited and named the overseer of the building of the Phyllis Wheatly YWCA in Washington D.C. Elizabeth’s community work seemed to never end. She was instrumental in helping the New Bedford Home for the Aged be constructed, by ensuring it was funded and contributing to the design of the organization's final and main location. To help maintain the several locations for the New Bedford Home for the Aged, Elizabeth arranged for the Women's Loyal Union to become the organization responsible for maintaining the locations. In typical Elizabeth Carter fashion, she became the president of the New Bedford Home for the Aged and the Women’s Loyal Union, maintaining those roles until 1930. The year earlier, she married a man named W. Sampson Brooks, the bishop of the African Methodist Episcopal Denomination of the Bethel Church. The two were married for five years before W. Sampson Brooks passed away. The couple moved to San Antonio, Texas, but Elizabeth moved back to New Bedford after her husband's death. The love for architecture never left Elizabeth’s heart. She would take on the task of preserving historical black properties and buildings in 1939. Elizabeth purchased and memorialized the home of the black military officer and hero William Carney. Elizabeth Carter Brooks died in 1951 in New Bedford, but will forever be remembered as a pioneer, educator, architect, activist, organizer, historian, and champion for the human rights of black Americans. To Mrs. Elizabeth Carter Brooks, we proudly stand on your shoulders. J.A. Ward Click here to support the OTSOG book series. References: https://amsterdamnews.com/news/2020/12/17/elizabeth-carter-brooks-architect-and-womens-club/ https://aaregistry.org/story/elizabeth-carter-brooks-educator-and-preservationist-born/ https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Elizabeth_Carter_Brooks On June 29, 1867, Emma Azalia Smith was born in Murfreesboro, Tennessee, her parents were Henry B. and Corilla Smith. Henry worked as a blacksmith while Corilla was a school teacher and taught singing lessons. Corilla founded a school for formerly enslaved people and their children. On many occasions, during singing lessons, Corolla and her students were threatened by several white terrorist groups. To keep his family safe, Henry moved his family to Detroit, Michigan in 1870. While in Detroit, Emma became the first black student to attend public school. At age three, she began taking singing lessons and learning to play the piano. She developed her talent very quickly and was considered a child prodigy. To help bring money into her home, Emma would perform at high school dances. In addition to developing her musical talents, Emma was a brilliant student. In 1887, she completed the graduation requirements for her high school and the Washington Normal School. A year later she earned her teaching certificate and began teaching at Clinton Elementary School. While teaching, she also began taking French lessons. To pay for her singing and piano lessons, Emma continued to teach singing lessons, voice lessons, continued to perform her music, and give voice recitals for her students. Emma became a singer for the Detroit Musical Society, which helped to bring more attention to her talents. Because she was very fair-skinned, she was encouraged by other black people to pass as white and use the privilege, but she was too proud of who she was to pretend to be a white woman. In 1894, Emma Smith met and married a man named Edwin Henry Hackley. She quit her job as a teacher and moved to Denver, Colorado with her husband. Mr. Hackley was the co-founder of The Colorado Statesman, a newspaper publishing company and worked as a lawyer. He was the first black person admitted to the Colorado bar. Emma and Henry had similar goals, so they combined their talents to create the Imperial Order of Libyans, an organization working to eliminate racial injustices. In 1900, Edwin sold his portion of The Colorado Statesman. He used the money and co-founded the newspaper the Statesman-cum-Denver Star with his wife Emma. Unfortunately, Denver’s high altitude caused Emma to begin having health issues so severe that she was forced to move to Philadelphia. When she originally moved, her husband was still living in Denver, but he eventually moved to Philadelphia with Emma. To make a living, Henry found a job as a newspaper carrier while Emma gave singing lessons and became a music teacher. Later in 1900, Emma earned her bachelor's degree from the Denver School of Music, making her the first black person to graduate from the school. She would become the assistant choir director for one of Denver’s largest choirs and the director of her church’s choir. She was also trained to sing in the bel canto vocal style and used that style as a soprano in a Denver concert choir. Emma gained a reputation for using her music to promote black pride among the people who supported her music. The Denver Post newspaper once wrote an article highlighting how her music caught the attention of many black people. She used her voice and her pen to help educate black Americans about black history and black culture. She became the editor for the Statesman Exponent, the women’s section of the Colorado Statesman newspaper. She founded the Denver branch of the Colorado Women’s League. The Colorado Women’s League was founded to improve the living conditions of black women in Colorado. In 1901, Emma held her first performance on her tour as a singer, she also moved back to Philadelphia and became the music director at Philadelphia's Episcopal Church of the Crucifixion. In 1904, Emma founded the Hackley Choir, which was a 100-member choir. She organized festivals for folk music, introducing her community to folk music made by black people. She took voice lessons in Paris from a notable opera singer and vocal coach, Jean de Reszke. During this time, she was able to give voice training to legendary black musicians such as Marian Anderson and R. Nathaniel Dett. Emma would often hold benefit concerts to raise funds for students to receive vocal and musical training abroad. In 1912, Emma founded the Vocal Normal Institute in Chicago, Illinois. In 1916, she published her book The Colored Girl Beautiful and became a lecturer until her health began to decline. Emma Hackley died in December of 1922, as a woman who used her legendary vocals to inspire black people to learn more about themselves. She also wrote several newspaper and magazine articles to educate black people about black history. To Mrs. Emma Azalia Smith Hackley, we proudly stand on your shoulders. J.A. Ward Click here to support the OTSOG book series. References: https://www.historycolorado.org/story/stuff-history/2017/03/27/azalia-smith-hackley-musical-prodigy-and-pioneering-journalist https://www.blackpast.org/african-american-history/hackley-emma-azalia-1867-1922/ https://aaregistry.org/story/emma-hackley-promoted-racial-pride-through-black-music/ https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Emma_Azalia_Hackley 7/3/2022 Dr. Jose Celso Barbosa Alcala | An Afro-Puerto Rican Physician, Politician, and EducatorRead NowOn July 27, 1857, Jose Celso Barbosa Alacala was born in Bayamón, Puerto Rico, to a working class parents Hermógenes Barbosa and Carmen Alcalá. Hermogenes worked as a brick mason and was the overseer of a sugar mill in San Antonio, Puerto Rico. Barbosa grew up in an environment where he was encouraged to use his education to achieve greatness. He was a great student which allowed him to attend Puerto Rico’s most prominent Jesuit seminary school. Barbosa graduated from the Jesuit seminary school in 1875, making him the first person of African descent to graduate from the seminary. Soon after graduation, Barbosa began working as a tutor for the children of his father's boss to pay for college. He was an excellent tutor, in addition to being a great student and a great young man. He was so impressive that his father’s boss decided to help Barbosa pay to attend college. After saving enough money to pay for college, Barbosa moved to New York City in 1875 to attend a prep school. At this prep school, Barbosa was able to become fluent in speaking English, fluent enough for Barbosa to attend college in the United States. Barbosa experienced a change of fate within his educational career that affected his life for the better. He became sick with pneumonia in 1876 while living in New York. After being diagnosed by his doctor, he was encouraged to study medicine, Barbosa's original plan was to study law. Later in 1876, Barbosa began attending Fort Edward College in New York. In 1877, he applied to attend the College of Physicians and Surgeons at Columbia University but was denied admission. Some sources say he was denied because he was a black man. He would later apply to attend the University of Michigan’s Medical School and was accepted. In 1880, Jose Barbosa graduated as the first person of Afro-Puerto Rican descent from the University of Michigans Medical School. He not only graduated with his medical degree, but he graduated as Valedictorian. Shortly after graduation, Dr. Barbosa returned to Puerto Rico to practice medicine with his people. He opened a practice in Bayamon, his hometown, and developed a reputation for providing great medical care to poor Afro-Puerto Rican people. His reputation reached the Spanish authorities, who quickly refused to recognize his medical credentials. At the time, the Spanish authorities only acknowledged medical degrees from Spain. With his medical practice in jeopardy of being shut down, Barbosa reached out to, and received help, from the American counsel. After a heated panel discussion, Dr. Barbosa was allowed to continue to practice medicine in his hometown. He became a member of Logia Estrella de Luquillo Masonic Lodge in 1885. Dr. Jose Barbosa married a woman named Jacinta Belén Sánchez Jiménez in 1887, they produced 11 children. He became an educator in 1888, teaching anatomy, obstetrics, midwifery, and natural science at the Puerto Rican Athenaeum, Puerto Rico’s oldest cultural institution. Later in 1888, Dr. Barbosa became the Under-Secretary of Education for Puerto Rico. Dr. Barbosa is credited with developing a prototype of a health insurance system, the first credit union in Puerto Rico, and establishing a worker’s cooperative called El Ahorro Colectivo in 1893. Dr. Barbosa became active in Puerto Rico’s political movement in 1883, by becoming involved with various political parties he either founded or became a member of. He founded the Puerto Rican Republican Party in 1899 as an advocate for Puerto Rico becoming free from Spanish rulership. He wanted Puerto Rico to have the freedoms of the United States and supported the U.S. annexation of Puerto Rico. Dr. Barbos’a political ideas and activism garnered him the title of “Father of the Puerto Rican Statehood Movement.” He also founded Puerto Rico’s first bilingual newspaper El Tiempo in 1907. Dr. Barbosa was receiving much support from fellow Afro-Puerto Ricans, they even joined his Republican Party because they believed in his political ideas of autonomy and independence from Spain. Dr. Barbosa became the first black person to be appointed to the Puerto Rican executive cabinet by four U.S. Presidents from 1900 to 1917. He was also elected to the Puerto Rican Senate in 1917 and served until 1921. Dr. Barbosa was inspired by African American abolitionists, educators, scholars, etc, he used that inspiration to continue providing great medical care to his people, use his political platform to help improve living conditions, and published forty years' worth of articles about civil rights and justice for Afro-Puerto Rican people, and African people throughout the diaspora. Dr. Barbosa was given the Cruz de la Orden del Mérito Naval award in 1898 and awarded honorary degrees from the University of Puerto Rico. Dr. Barbosa died on September 21, 1921, in San Juan, Puerto Rico. He dedicated over 30 years of his life to serving his people as a doctor, educator, and politician because he wanted his people to live free, healthy, and prosperous lives. To Dr. Jose Celso Barbosa Alcala, we proudly stand on your shoulders. J.A. Ward Click here to support the OTSOG book series. References: https://www.pr51st.com/untitled/ https://www.blackpast.org/african-american-history/jose-barbosa-1857-1921/ https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jos%C3%A9_Celso_Barbosa |

Details

Categories

All

Click Here to join our mailing list

|

Contact Us: |

Connect With Us |

Site powered by PIT Web Design

RSS Feed

RSS Feed