|

In 1935, Evelyn Ruth Backo was born in Ingham, Queensland, Australia; she is the granddaughter of a former slave who was kidnapped from the South Pacific nation of Vanuatu. Early in life Evelyn’s father gave her sound advice about challenging social injustices, he stated “If you don’t think something is right, then challenge it”, and challenge the system is just what she did. Evelyn married a man named Allan Scott who was the first person to introduce her to front line political activism; the seed that Allan planted would soon blossom. In the 1960’s Evelyn would move to Townsville which is a city in Queensland, Australia. While living in Townsville she was able to see indigenous people discriminated against with her own eyes, they faced discrimination in housing, health care, the education system and the employment sector. She witnessed the police abuse its power often by terrorizing the indigenous people. Witnessing these acts led her to becoming acquainted with her future mentor Joe McGuiness and fellow Townsville political activist Eddie Mabo. She worked at the Townsville Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Advancement League; the league was formed in 1957 to address issues of employment, housing, health and education. One of the issues Evelyn and the league faced was fighting the unjust Aborigines Protection Act, an act the declared aboriginals as minors who needed to be protected by the government, the act also stripped the people of their political rights. In 1967, she helped campaign for the Australian referendum which approved the amendments of sections 51 and 127 of the Australian constitution. The amendments stated that the aboriginals were now considered as a part of the Australian population and the federal parliament could create legislation specifically for the aboriginals. In 1971, she became an active member of the Federal Council for the Advancement of Aborigines and Torres Strait Islanders (FCAATSI), an organization where she served as the first general-secretary and vice-president. Equipped with a sound strategy, in 1973, the FCAATSI became an organization led by the ingenious people of Australia. She was a member of the National Aboriginal and Islander Council, the first national women’s organization founded in the 1970’s. Evelyn’s activism also extended to protecting her environment; helping to create protection for the Great Barrier Reef and the land she became a member of the Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority during the 1980’s. In 1977, Evelyn was awarded the Queen’s Jubilee Medal to acknowledge her work towards the advancement of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people’s rights. She was appointed as the Chairperson of the Council for Aboriginal Reconciliation in the 1990’s; at that time the challenge was the federal government actively cutting funding for the reconciliation. In 2003, she received the Queensland Greats award for her life-long work of fighting for the rights of aboriginal people. The Australian Catholic University awarded Evelyn an honorary doctorate degree in 2000, and James Cook University awarded her an honorary degree in 2001. Later in 2001 Evelyn was awarded as an Officer in the General Division of the Order of Australia; the award is an order of chivalry established on February 14, 1975 by Elizabeth II, Queen of Australia, to recognize Australian citizens and other persons for achievement or meritorious service. Evelyn was a true fighter for her people and she truly loved to company of her people. She had the ability to rub shoulders with dignitaries from across the world, but still found time to build with the indigenous people the white supremacist tried to destroy. Fishing was known to be one of her favorite activities when she wasn’t fighting for her people. Evelyn Scott died on September 21, 2017 at the age of 81 and her funeral was held as a state funeral; she was the first indigenous women to have a state funeral. Evelyn was determined to create change for the indigenous people of Australia as well as challenging the apartheid the black faced in South Africa. She gave herself to her people so the future of the indigenous people would be a future free of white supremacy. Evelyn Scott, we proudly stand on your shoulders. J.A. Ward References:

https://www.sbs.com.au/nitv/nitv-news/article/2017/09/21/community-mourning-after-activist-and-leader-dr-eveleyn-scott-passes-away https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Evelyn_Scott_(activist) http://www.theaustralian.com.au/national-affairs/indigenous/evelyn-scott-indigenous-activist-dies-in-queensland/news-story/ee982698ec1ea478d0fe003500e3aa38

10 Comments

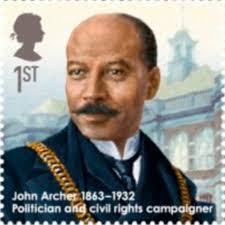

John Richard Archer was born on June 8th, 1863 in Liverpool, England; his parents were Richard Archer and Mary Burns. Richard Archer was a black man from Barbados and Mary Burns was and Irish woman living in England. Archer was able to see the world when he joined the British Navy, as a seaman his travels would allow him to take up residence in the United States and Canada. While living in Canada Archer would meet and marry a black Canadian woman named Bertha. He also opened a small photography shop during the time when photography was only around roughly 60 years (Photography was introduced to the world in 1939). Archer gained an interest in the local politics of London by becoming acquainted with the social activists who were labeled “radicals”. This affiliation led Archer to being elected as the Progressive to the Battersea Borough Council for the Latchmere ward in 1906. As the progressive to Battersea, he successfully campaigned for a minimum wage of 32 shillings a week for the council workers. Unfortunately, he was not reelected as the progressive until 1909, but his campaign in 1912 allowed him to once again be elected as the Progressive for Battersea. In 1913, Archer was nominated and won the election for the seat as the mayor of Battersea, London. Archer was the first black mayor in London’s history, but the second black British Mayor. Archer quoted the following during his victory speech: “My election tonight means a new era. You have made history tonight. For the first time in the history of the English nation a man of color has been elected as mayor of an English borough. “That will go forth to the colored nations of the world and they will look to Battersea and say Battersea has done many things in the past, but the greatest thing it has done has been to show that it has no racial prejudice and that it recognizes a man for the work he has done.” In 1919, he was re-elected to the Battersea Counsel but he was representing the Labor Party, which was a broad church bringing together an alliance of social-democratic, socialist and trade-unionist outlooks. He would become the president of the African Progress Union in 1918, a union that worked for black equality and empowerment in London. In 1919, he served as a British delegate to the Pan-African Congress in Paris, France; he would follow this event with his own Pan-African Congress in London two years later. In 1922, Archer would step down from his position as progressive of the Battersea Borough Council to help Shapurji Saklatvala campaign for the position. He used his influence to convince the Labor Party to endorse Saklatvala while he became one the first black members of parliament in London’s history. Saklatvala was a communist activist standing for parliament in North Battersea before collaborating with Archer, he became the Progressive for Battersea in 1922 and 1924 with the help of Archer. The Labor Party would eventually split shortly after 1924; Archer would become the agent for the person who defeated Saklatvala in the 1929 election for the Progressive of Battersea. Later in his life Archer would become the governor of the Battersea Polytechnic Institute, which is now The University of Surrey, a public research university located in Guildford, Surrey, in the South East of England, United Kingdom. He would also become the President of the Nine Elms Swimming Club, Chair of the Whitley Council Staff Committee, and a member of the Wandsworth Board of Guardians. In 1931, he was reelected for the Nine Elms Award just before his death in July of 1932. During the time of his death he was the deputy leader of the Battersea counsel. Archer was following in the footsteps of Mr. Allen Glaisyer Minns, the first black British mayor. Archer used his platforms to help fight for justice and equality for the black people of London. He believed in challenging the system to get results that helped change the conditions of his people. Black British history is not taught at all within our school systems or any other historical medium, it is a great tragedy because we are unaware of the struggles and accomplishments of our people across the pond. The story of Archer is an example of black excellence in Europe, as well as, a reminder of how much more we have to learn about our history. Mr. John Richard Archer, we proudly stand on your shoulders. J.A. Ward Wangari Muta Maathai was born on April 1st, 1940 in the village of Ihithe in the Nyeri District of Kenya. Around 1943, her family moved to a White-owned farm where her father found work, she lived there until 1947 when her mother returned to Ihithe so 2 of her brothers could attend school (there was no schooling on the farm). At the age of 8, she joined her brothers in Primary school and at the age of 11, she moved to St. Cecilia’s Intermediate Primary School, which was a catholic boarding school in Nyeri. She spent four years at the school becoming fluent in English and converting to Catholicism. While at Cecilia’s she was protected from the Mau Mau Uprising that caused her mother to move to an emergency village. She graduated first in her class and was admitted to Loreto High School in Limuru, the only Catholic High School for Girls in Kenya. As colonialism ended in East Africa, Kenyan Politicians began to look for ways to make education in Western Nations available, and with the help of Senator John Kennedy, the Kennedy Airlift Program was created. Maathai was one of roughly 300 Kenyans selected to study in the United States in September of 1960. She received a scholarship to Mount St. Scholastica College (what is now Benedictine College) where she majored in biology and minored in chemistry and German receiving her degree in 1964. She then went on to the University of Pittsburgh to receive her master’s degree in biology, she also had her first experience with environmental restoration working with local environmentalists pushing for air pollution control in the city. After graduating from Mount St. Scholastica College in 1966 she was appointed as a research assistant to a professor of zoology at the University College of Nairobi. However, she returned to Kenya only to find that her position had been given to someone else, a move that she believed was caused by her gender and her tribe. After months of searching, she was finally given another job as a research assistant in the microanatomy section of the Department of Veterinary Anatomy, in the School of Veterinary Medicine at the University College of Nairobi. That same year she meet and married Mwangi Maathai (a Kenyan who had also studied in America), they rented a small shop to start a general store and employed her sisters. In 1967, she traveled to Germany to pursue her doctorate but returned to Nairobi in May of 1969 married, and later that same year became pregnant with her first child while her husband campaigned for a seat in Parliament. In 1971, she received her Ph.D. in Veterinary Anatomy becoming the first Eastern African Woman to do so; she also had her second child. By 1975, Wangari became a senior lecturer in anatomy at Nairobi, she would also become the chair of the department of Veterinary Anatomy in 1976, an associate professor in 1977, and was the first woman to hold any of these titles. She was also campaigning for equal benefits for women as she worked on the staff of the university. She made the attempt to convert the Academic Staff Association into a union and was denied by the courts, but many of her demands were met. She also became involved in a lot of off-campus organizations in the early 1970s. She became the director of the Kenya Red Cross Society in 1973, a member of the Kenya Association of University Women, and would eventually become the board chair of the Environment Liaison Centre to name a few. Through her work, it became clear to her that most of Kenya’s problems could be attributed to environmental degradation. In 1974, she would give birth to her third child. During this time her husband campaigned for Parliament and won on the promise of finding jobs. This caused her to connect her activism with employment options and led to the creation of Envirocare Ltd., which was a business centered around getting ordinary people to plant trees. The project failed with numerous problems mostly centered on funding but it helped her make important connections. During a speech to the National Council of Women of Kenya she proposed further tree planting, and on June 5th, 1977 marking World Environment Day, the NCWK marched from Kenyatta International Conference Centre to Kamukunji Park, there they planted 7 trees in honor of the historical Community leaders. This marked the first Green Belt known at the time as the Save the Land Harambee. She encouraged many women to plant trees by searching the forest for seeds native to the region and replanting them. She agreed to pay the women a stipend for each seedling they planted. In 1979, after a 2-year separation, she divorced her husband. Her husband cited that she was cruel and an adulteress. It is believed that he thought she was too strong-willed for a woman and uncontrollable. In an interview after the trial, she accused the judge of being incompetent and corrupt, which landed her in jail with a 6-month sentence for contempt of court, however, she only served 3 days. Her husband also sent her a letter demanding that she drop his surname however she chose to add an extra “a” to the name instead of dropping the name. Facing financial hardships she accepted a job with the Economic Commission for Africa, and because of the travel it required she had to send her children to live with her ex-husband. After the divorce she decided to run for chairperson of the National Council of Women of Kenya, however the president of Kenya wanted to limit the power of people from her Kikuyu Ethnicity. Because he did not support her bid she ended up losing by 3 votes, and eventually accepted the position of vice-chairman. The following year she ran for chairman again and won the election, the organization soon found all of its funding dried up and began facing bankruptcy. The NCWK survived through her leadership and she remained chairwoman until she retired in 1987. In 1982, she ran for Parliament which required her to quit her job at the university. She was declared ineligible after filing an appeal which she lost, she would attempt to get her job back but was denied, and she was eventually evicted from her home because she lived in staff housing and was no longer on the staff. During this time she moved into a home she purchased years before and began working on the Green Belt Movement. After linking with a Norwegian Forestry Society and receiving funding from the United Nations Voluntary Fund for Women, she had the capital to refine her operation, hire staff, and continue paying the women for the planting of trees, along with the husbands and sons that were tracking the plantings. Maathai found herself again in a hot seat when she along with her organization began to take democratic stances that conflicted with the government. She publicly denounced the government as carrying out electoral frauds to remain in power. She also engaged in a very public battle to prevent the construction of a 60-story Kenya Times Media Trust Complex in Uhuru Park. In addition to being the new home for Kenyan News outlets, the complex was also intended to house shopping malls, auditoriums, and a large statue of the president of Kenya. During this feud, she wrote letters of protest to the president’s office and anyone else that had a mailbox, including Sir John Johnson and the British High Commissioner in Nairobi. The government did not respond to her letters but attacked her in the media labeling her as a crazy woman. The government also attacked her for writing to foreign nations, it called the Green Belt Movement a bogus organization suggesting that if she was so comfortable writing to Europeans then she should go live in Europe. The project was eventually canceled because of international pressure largely centered on Maathai. Maathai and the movement continued to grow and become an international force, although at odds with the Kenyan Government. In 1999, she found herself and her organization at the center of an international protest to prevent the Kenyan government from giving public land to political supporters. Her movement won the day regarding that specific incident. In 2002, after many years of trying, she finally managed to unite opposing parties to the ruling party under one roof and won a seat in Parliament with 98% of the vote. In 2004, Maathai was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize for her fight to gain sustainable development, democracy, and peace. She was later appointed Assistant Minister in the Ministry for Environment and Natural Resources. She was also responsible for planting over 35 million trees, founding the Mazingira Green Party, and continuing to fight for what she believed in until she died from complications regarding ovarian cancer in 2011. Professor Wangari Muta Maathai, we proudly stand on your Shoulders. Patrick Irvine Click here to support the OTSOG book series. |

Details

Categories

All

Click Here to join our mailing list

|

Contact Us: |

Connect With Us |

Site powered by PIT Web Design

RSS Feed

RSS Feed