|

Born September 17, 1879, in Calvert, Texas, to parents Sarah and Andrew Foster, he is known as the “father of black baseball” because of his pioneering spirit. In 1897 Foster began his baseball career at the age of 18 with the Waco Yellow Jackets, which was an independently owned black baseball team. Over the next three years, Foster showed brilliance and skills as he marveled the crowds. His performances earned him a reputation as a great baseball player, and also a spot on one of the top black baseball teams the Chicago Union Giants in 1902. As Foster began playing with Chicago he got off to a rough start and was released by the team. He would later sign with a semipro baseball team located in Ostego, Michigan; Bardeen’s Ostego Independents in 1902. During Fosters time with the Independents, he played twelve games and earned a record of eight wins and four loses and eighty-two strikeouts. Five of the games foster played in his strikeouts were not recorded, but it is stated that he totaled over one hundred strikeouts in the twelve games. After the 1902 season Foster joined the best black baseball team around, the Cuban X-Giants based in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. His reputation as a great pitcher was growing more with every game played; he is noted for his performance in a black eastern championship game against the Philadelphia Giants. Foster was responsible for four of the teams five victories to win the series. Andrew Foster would become “Rube” Foster after defeating Rube Waddell in an exhibition game against the Philadelphia Athletics. Rube Waddell was a well-known left handed pitcher who was considered the best until he faced Foster. In 1904 Foster joined the Philadelphia Giants winning twenty games against black and white teams and only suffered six defeats. His two no-hitters and a .400 batting average helped him lead his team to the championship over his old team the Cuban X-Giants. The following seasons Foster lead his team to another championship compiling a fantastic 51-4 record as a starting pitcher. In 1906 Foster and the Philadelphia Giants would lead the charge in forming the International League of Independent Baseball Players, a league of both black and white players. In 1907 Sol White the manager of the Philadelphia Giants, published his Official Baseball Guide: History of Colored Baseball. Foster contributed to the guide by writing an article titled “How to Pitch”; following the publication Foster and other players left Philadelphia and joined the Chicago Leland Giants. Foster would be named playing manager of the team, under his management the team won one hundred eleven games and only lost ten. The next season Fosters team tied with the Philadelphia Giants in the championship series, he was off to a great start as a manager. In 1916 Foster, I.C. Taylor, and team owners attempted to form an all-black baseball league but they could not agree to terms. At this time in fosters career he was more of a manager than a player, he would eventually became a full-time manager. Many of fosters former players went on to become managers themselves. In 1919 Foster had a hand in financing the Detroit Stars; with the Stars he developed more players into managers. Most historians believe Foster was preparing these managers so he could create an all-black baseball league. 1920 was a year to be remembered, this was the year of the formation of the Negro National League. Foster, Taylor, and six other team owners met and came to terms for the formation of the league. Foster was named president of the NNL and managed his team the American Giants. As time passed the Hilldale Club and the Bacharach Giants, left the NNL and formed their own league, the Eastern Colored League. The NNL would lose players to the ECL but the two leagues agreed to respect the player’s contracts and play a World Series. Foster would suffer a tragic accident in 1926 and almost lost his life. Along with the accident, Foster was suffering from a mental illness and was institutionalized in Kankakee, Illinois. The league would start to collapse with the absence of foster; at the same time fosters health began to decline. Foster would die in 1930, leaving behind a proud legacy. Unfortunately the NNL would collapse in 1931 under new management. In 1981 Foster was elected to the Baseball Hall of Fame as the first representative of the Negro Leagues. Every September the Negro Leagues Baseball Museum hosts its annual Andrew “Rube” Foster lecture, highlighting his life and legacy. Rube Foster was an innovator and an example of true entrepreneurship; he was a person to be celebrated. He created a means for black baseball players to have a league of their own to thrive as baseball players. The formation of the Negro National League shows Fosters proactive spirit; he was not waiting on white teams to give him a chance. Andrew “Rube” Foster, we stand on your shoulders. J.A. Ward. Click below to watch the Rube Foster video

0 Comments

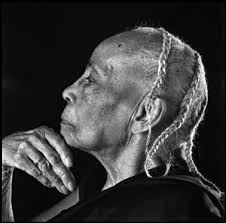

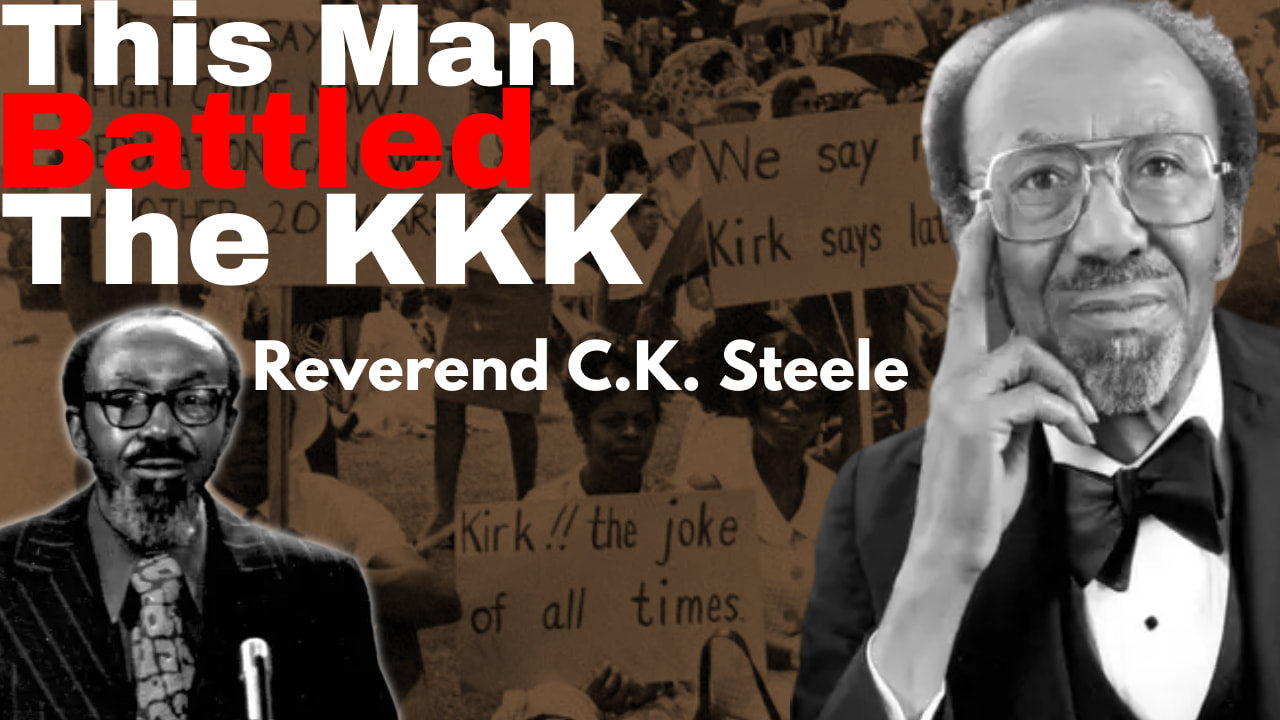

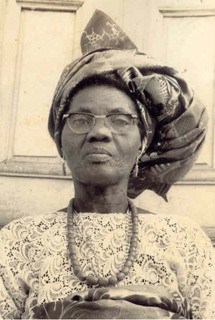

Born May 3, 1898 in Charleston, South Carolina during the reconstruction era, her parents were Peter and Victoria Poinsette. Clark grew up in a very strict household her mother was determined to make her and her sisters ladies. Clark however would rebel against her mother’s wishes, but a bright future was still ahead of her. Her educational career started in 1904 at the Mary Street School, which was a challenging start to her educational career. Clark was not learning anything attending that school, so her mother quickly took her out of the school so she could learn. There was not a high school available for black students before 1914 when a school opened up for 6th, 7th and 8th grades. After the eighth grade Clark attended Avery High School which was an all-white school with white female teachers until 1914. In 1916 Clark graduated from high school but could not attend college right away because of financial problems. As an eighteen year old she became a teacher on John’s Island at the Promise Land School from 1916 to 1919, she then taught at Avery High School from 1919 to 1920. Clark kept her eye on her own educational pursuits and finally attended Benedict College in 1942 and received her B.A. Her next step in life was to gain her M.A. from Hampton University in 1944. Because she was a black women she was not allowed to teach in the South Carolina public school district, but she was able to teach within the rural school district on John’s Island. Clark would teach children during the day and would teach adults at night, her teaching experience helped her create quicker ways to teach adults the art of reading and writing. Clark began to notice the unequal terms in which black schools operated compared to white schools. The unequal treatment of the school systems lead Clark directly into the civil rights movement, fighting for equal rights for blacks within the school systems. In 1919 Clark was introduced to the NAACP while attending a meeting on John’s Island, she would later join the Charleston chapter of the NAACP while teaching at the Avery Normal Institute a private black school. Clark took her activism to another level when she led her students around Charleston to collect 10, 000 signatures to allow black principles at Avery. She was able to gather 10,000 signatures in one day and black principles were admitted. In 1920 she met her future husband Nerie Clark; they courted for three years before getting married in 1923. Clark returned to college and earned a bachelor’s degree from Columbia University and in 1947 Clark began teaching in the Charleston, South Carolina school system. She was an active member of the Charleston YMCA, and she was the chairperson of the Charleston NAACP. In 1956 she became the vice president of the Charleston NAACP, later that year the South Carolina legislature passed a law banning state employees from joining any civil rights organizations. Clark was not afraid to lose her job, so she did not relinquish her NAACP membership. She was later fired and black balled from the Charleston school system. Clark would later find work with the Highlander Folk School in Monteagle, Tennessee, as a full-time director of literacy workshops. In 1959 Clark was arrested for allegedly possessing whiskey, but the charges were later dropped because of a lack of evidence. Clark took the concept of the workshops and spread the program teaching blacks how to fill out driver’s licenses exams, voter registration forms, sears mail-order forms, and how to fill out and sign checks. Later Clark served as a recruiter for Highlander, recruiting such talents as Rosa Parks, and other members of the bus boycott. Clark created “citizenship schools,” which were used to teach literacy to adults in the south. The success of the “citizenship schools” came because of the brilliance of Septima Clark; she combined relevant issues with the needs of the students. Her methods allowed her to empower the communities she taught in, thus making the community members an asset to their communities. The schools began to spread to other southern states, but they faced financial troubles because its principle funder Highlander faced financial troubles. Clark’s program would later gain financing from the SCLC who had a bigger budget. Under the SCLC the program was able to train over 10,000 school teachers, who taught over 25,000 students. As a result of the first session of classes 37 new voters were able to register to vote in 1958. By 1969, 700,000 blacks became registered to vote because of the program. Clark would eventually earn the position of director of educating and teaching in the SCLC, becoming the first woman to hold a position on the board of the SCLC. Clark worked with the Tuberculosis Association and the Charleston Health Department, and was an active member of the Alpha Kappa Alpha sorority. She retired from the SCLC in 1970; she later sought reinstatement of pension and back salary from her firing from the Charleston County school board in 1956. She won her reinstatement and later served two years on the Charleston County School Board. Septima Clark died in 1987 but her legacy will live forever. She was awarded a Living Legacy Award in 1979 by President Jimmy Carter, and was awarded the SCLC’s highest award the Drum Major for justice award. Clark wrote two autobiographies, Echo in My Soul in 1962, and Ready From within in 1979. Clark was dynamic, fearless and brilliant. She found a productive way empower her people through education to help them have a political voice. She stood up against injustices from childhood to her death. Mrs. Septima Poinsettia Clark, we are honored to stand on your shoulders. J.A. Ward. View Septima Clark video below Rev. Charles Kenzie Steele was born on February 17, 1914, in Gary, West Virginia; his parents were Lyde Bailor and Henry L. Steele. As a young promising leader, Rev. Steel began preaching at the age of 15, and by the age of 21, he became an ordained minister. He put forth the effort to earn a BA degree from Morehouse College three years after he became an ordained minister. He began serving as a minister at Friendship Baptist Church in Northeast Georgia, after a year his services were requested at Hall Street Baptist Church in Montgomery, Alabama in 1939. In 1941, Rev. Steele had the privilege of meeting the love of his life Lois Brock, who he would later make his wife. After 9 years of service in Montgomery, he was called to serve at Springfield Baptist Church in Augusta, Georgia. Four years later he moved again to Tallahassee, Florida to serve at Bethel Baptist Church in 1952. Rev. Steele became the head of the Tallahassee chapter of the NAACP; he also was elected president of the Inter Civic Council in 1956. Under Rev. Steele’s leadership, the Inter Civic Council was created to help direct a bus boycott, which was started by students at Florida A&M University. The Inter Civic Council gathered leaders from the community to organize a carpool as they demanded full integration of the bus system. As the bus boycott began the members of the carpool were harassed by the police department, and 22 members were charged by city officials for operating a transportation system without a franchise. The Inter Civic Council levied an $11,000 fine on city officials in an attempt to disband the boycott. The members of the boycott would not allow their efforts to be stopped; they began walking where they needed to go. In 1956, Rev. Steele joined Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr as one of the speakers at nonviolence workshops hosted by the Tuskegee Institute. Steele spoke at the annual meeting of the National Baptist Convention, and the Montgomery Improvement Association’s Institute on Nonviolence and Social Change. In 1957 Steele attended the founding meeting of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference; during the meeting, Steele would be elected vice president of the SCLC. In 1962 Steele led the SCLC in a demonstration in Albany, Georgia as vice president while Dr. King was incarcerated. Steele became an active contributor to the Poor People's Campaign, he also led a “Vigil for Poverty” in Tallahassee, FL to recognize and help persons who lacked basic needs. After the death of Dr. King, Steel remained an active force in the fight for equality and justice in Tallahassee. On August 19th, 1980, Rev. Steele gave way to his battle with cancer but his legacy never died. When a bus terminal was created in Tallahassee, FL it was named after Rev. Steele and a statue of him was erected. At that time a statue of a black man was the only statue of a person’s likeness, in the capital city of the State of Florida. Later in 1980, Florida State University bestowed upon Rev. Steele an Honorary Doctor of Humane Letters Degree, Rev. Steele was the first black to have an honorary degree bestowed upon him by Florida State University, and he was the first black to have that particular degree honored to him. Before his death, he established a charter school in Tallahassee, FL the Steele-Collins Charter School, which was also named after former governor Leroy Collins. Rev. Steel was a pastor for 28 years at Bethel Baptist Church, in his time he fought hard for social change in Tallahassee, FL as well as the south. Rev. Steel faced death and many incarcerations to help blacks receive humane treatment from their white counterparts. Rev. Steele made Tallahassee, FL, and every other city he lived in a better place for blacks to live because of his actions and relentlessness. Rev. Charles Kenzie Steele, we stand on your shoulders. J.A. Ward. Click here to support the OTSOG book series On October 25, 1900 Francis Abigail Olufunmilayo Thomas was born in Abeokuta, Nigeria, to parents Daniel Olumeyuwa Thomas and Lucretia Phyllis Omoyeni Adeosolu. Kuti attended grammar school as a child in Abeokuta; she furthered her studies as a teen and young adult in England. As she completed her studies in England she returned home to serve as a teacher in her city. Around January of 1925, she married a man named Reverend Israel Oludotun Ransome Kuti. Mr. Kuti was a noble man who fought for equality for his people and he successfully established the Nigeria Union of Teachers and the Nigerian Union of Students. In 1965 Funmilayo Kuti received a national honor of membership within the Order of Nigeria; the honors were instituted by the National Honors Act No. 5 of 1964, during the Nigerian First Republic to honor Nigerians who have rendered service to the benefit of the nation. In 1968 she received an honorary doctorate of laws from the University of Ibadan. Kuti was a renowned activist and noted educator, as well as a leader within the women’s rights movement along with Elizabeth Adekogbe during the 1950’s. Kuti would also establish a women’s organization for the women in Abeokuta which holds a membership of over 20,000 women from all walks of life. Her next step was to raise public awareness about women’s rights when it comes to unfair pricing towards female merchants, the prices were not even and trade was a major economic component of the city. Kuti started the public protesting against the native authorities and the Alake of Egbaland; she presented the authorities with documents proving abuse by the Alake authorities. The documents proved that the Aleke granted Colonel Suzerain a member of the Government of the United Kingdom, the right to collect taxes. A separate tax rate was given to Nigerian women; as a result of the documents the tax rates were abolished and Colonel Suzerain gave up his position. Kuti founded the Federation of Nigerian Women Societies; the federation would later merge with the Women’s International Democratic Federation. As a long-time member of the National Council of Nigeria and the Cameroons, she advocated strongly for women’s rights. Kuti was subsequently expelled from the organization when she was not elected to a federal parliamentary seat. The spirit and will to fight for human rights earned Kuti an elected seat within the Nigerian House of Chiefs. Kuti was a world traveler but her travels caused the Nigerian Government to question her moves. She visited the USSR, Hungary, and China; because of this her passport was not renewed by her government. Her travels also caused the United States to refuse her entrance into the country. Kuti would later become one of the delegates who negotiated Nigeria’s independence from the British Government. In 1978 Funmilayo Kuti was thrown from a second floor window when her son Fela Kuti’s compound was raided by military personnel. She would later die as a result of her injuries on April 13, 1978. August of 2012, Funmilayo Kuti’s grandson Seun Kuti demanded an apology from the Nigerian government for the death of his grandmother, before they used her likeness on the N5000 Note which is Nigerian currency. Kuti was a dynamic woman who dedicated her life to helping others and fighting injustices, all while raising three remarkable sons. She was brilliant, relentless, fierce and nurturing. She helped make the life easier for Nigerian women by either starting or becoming a part of a number of women rights organizations. Funmilayo Ransome- Kuti, we stand on your shoulders. J.A. Ward. View the Funmilayo Ransome-Kuti video below |

Details

Categories

All

Click Here to join our mailing list

|

Contact Us: |

Connect With Us |

Site powered by PIT Web Design

RSS Feed

RSS Feed