|

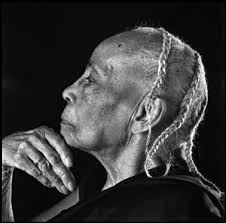

Born May 3, 1898 in Charleston, South Carolina during the reconstruction era, her parents were Peter and Victoria Poinsette. Clark grew up in a very strict household her mother was determined to make her and her sisters ladies. Clark however would rebel against her mother’s wishes, but a bright future was still ahead of her. Her educational career started in 1904 at the Mary Street School, which was a challenging start to her educational career. Clark was not learning anything attending that school, so her mother quickly took her out of the school so she could learn. There was not a high school available for black students before 1914 when a school opened up for 6th, 7th and 8th grades. After the eighth grade Clark attended Avery High School which was an all-white school with white female teachers until 1914. In 1916 Clark graduated from high school but could not attend college right away because of financial problems. As an eighteen year old she became a teacher on John’s Island at the Promise Land School from 1916 to 1919, she then taught at Avery High School from 1919 to 1920. Clark kept her eye on her own educational pursuits and finally attended Benedict College in 1942 and received her B.A. Her next step in life was to gain her M.A. from Hampton University in 1944. Because she was a black women she was not allowed to teach in the South Carolina public school district, but she was able to teach within the rural school district on John’s Island. Clark would teach children during the day and would teach adults at night, her teaching experience helped her create quicker ways to teach adults the art of reading and writing. Clark began to notice the unequal terms in which black schools operated compared to white schools. The unequal treatment of the school systems lead Clark directly into the civil rights movement, fighting for equal rights for blacks within the school systems. In 1919 Clark was introduced to the NAACP while attending a meeting on John’s Island, she would later join the Charleston chapter of the NAACP while teaching at the Avery Normal Institute a private black school. Clark took her activism to another level when she led her students around Charleston to collect 10, 000 signatures to allow black principles at Avery. She was able to gather 10,000 signatures in one day and black principles were admitted. In 1920 she met her future husband Nerie Clark; they courted for three years before getting married in 1923. Clark returned to college and earned a bachelor’s degree from Columbia University and in 1947 Clark began teaching in the Charleston, South Carolina school system. She was an active member of the Charleston YMCA, and she was the chairperson of the Charleston NAACP. In 1956 she became the vice president of the Charleston NAACP, later that year the South Carolina legislature passed a law banning state employees from joining any civil rights organizations. Clark was not afraid to lose her job, so she did not relinquish her NAACP membership. She was later fired and black balled from the Charleston school system. Clark would later find work with the Highlander Folk School in Monteagle, Tennessee, as a full-time director of literacy workshops. In 1959 Clark was arrested for allegedly possessing whiskey, but the charges were later dropped because of a lack of evidence. Clark took the concept of the workshops and spread the program teaching blacks how to fill out driver’s licenses exams, voter registration forms, sears mail-order forms, and how to fill out and sign checks. Later Clark served as a recruiter for Highlander, recruiting such talents as Rosa Parks, and other members of the bus boycott. Clark created “citizenship schools,” which were used to teach literacy to adults in the south. The success of the “citizenship schools” came because of the brilliance of Septima Clark; she combined relevant issues with the needs of the students. Her methods allowed her to empower the communities she taught in, thus making the community members an asset to their communities. The schools began to spread to other southern states, but they faced financial troubles because its principle funder Highlander faced financial troubles. Clark’s program would later gain financing from the SCLC who had a bigger budget. Under the SCLC the program was able to train over 10,000 school teachers, who taught over 25,000 students. As a result of the first session of classes 37 new voters were able to register to vote in 1958. By 1969, 700,000 blacks became registered to vote because of the program. Clark would eventually earn the position of director of educating and teaching in the SCLC, becoming the first woman to hold a position on the board of the SCLC. Clark worked with the Tuberculosis Association and the Charleston Health Department, and was an active member of the Alpha Kappa Alpha sorority. She retired from the SCLC in 1970; she later sought reinstatement of pension and back salary from her firing from the Charleston County school board in 1956. She won her reinstatement and later served two years on the Charleston County School Board. Septima Clark died in 1987 but her legacy will live forever. She was awarded a Living Legacy Award in 1979 by President Jimmy Carter, and was awarded the SCLC’s highest award the Drum Major for justice award. Clark wrote two autobiographies, Echo in My Soul in 1962, and Ready From within in 1979. Clark was dynamic, fearless and brilliant. She found a productive way empower her people through education to help them have a political voice. She stood up against injustices from childhood to her death. Mrs. Septima Poinsettia Clark, we are honored to stand on your shoulders. J.A. Ward. View Septima Clark video below

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Details

Categories

All

Click Here to join our mailing list

|

Contact Us: |

Connect With Us |

Site powered by PIT Web Design

RSS Feed

RSS Feed