|

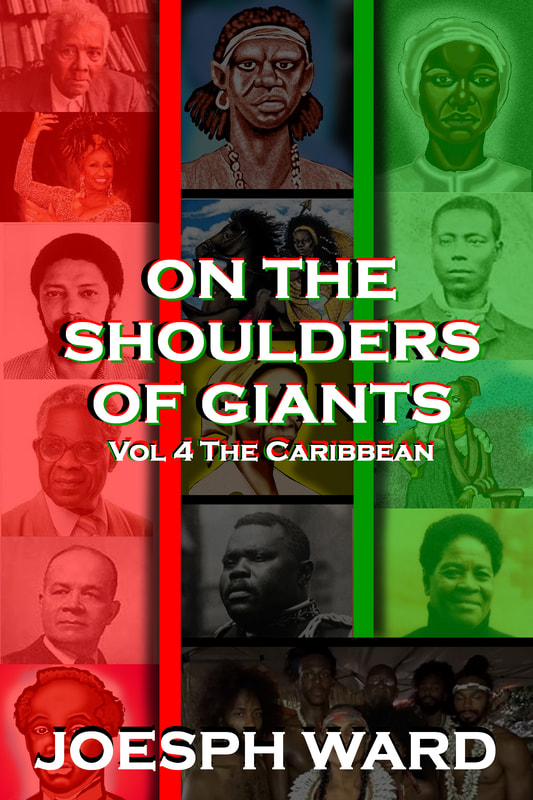

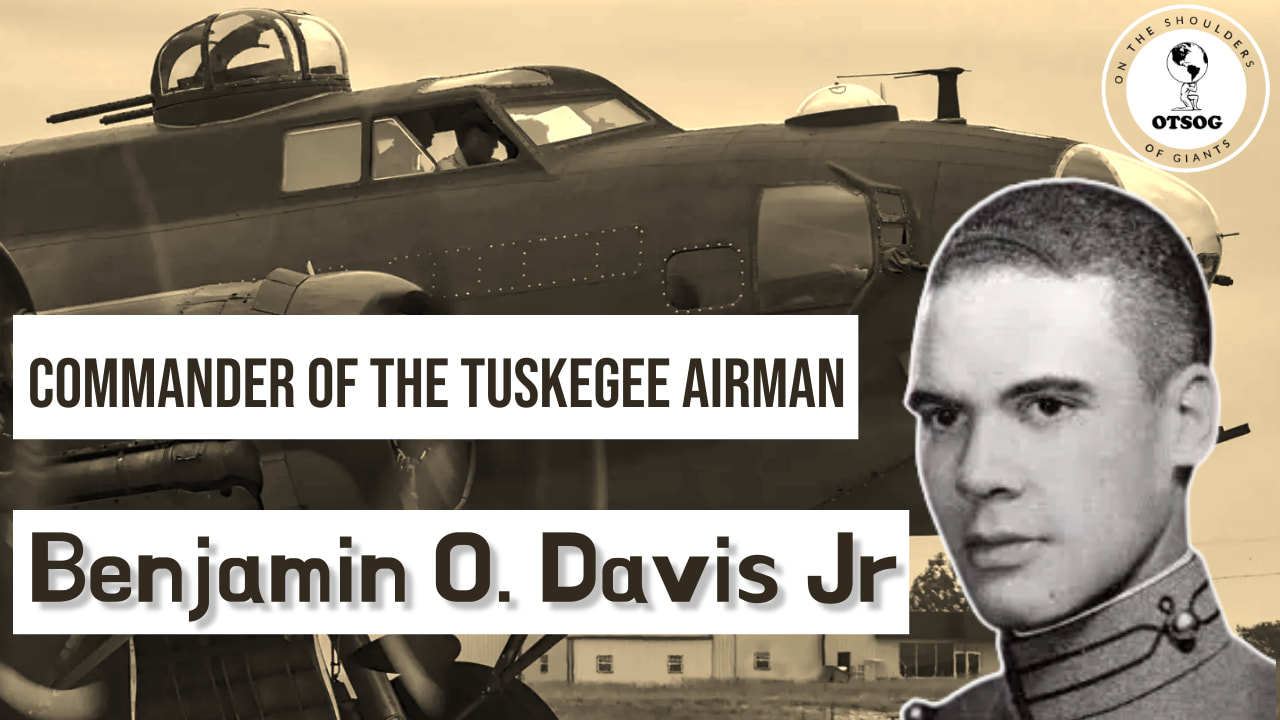

On December 18, 1912, Benjamin O. Davis, Jr. was born in Washington, D.C. His father was Benjamin O. Davis, Sr., a U.S. Army brigadier general who served 41 years in the military. Benjamin Jr’s mother was named Elnora Dickerson Davis. Not much information is available about her life. She was a mother and a wife who died in 1916 after giving birth to her third child. Benjamin Davis, Sr. taught his son about racism and to not allow anyone or anything to prevent him from being successful. Benjamin Davis, Jr’s interest to become a piolet was piqued at the age of 13 being able to fly along with a barnstorming piolet in Washington, D.C., from then on he was focused on becoming a pilot. In 1929, Davis graduated from high school in Cleveland, Ohio during the Great Depression, after graduating from Central High School, he began attending Western Reserve University, a research university in Cleveland. He would soon leave Western Reserve and attend the University of France and the University of Chicago, before attending the United States Military Academy at West Point in 1932. Racism, discrimination, and isolation are three words to describe what Davis experienced while attending West Point. His white classmates refused to speak to him, refused to become his roommate, and refused to offer any help to a fellow academy member. Davis was completely on his own as a cadet. His white academy members only talked to him in the line of duty. Despite the discriminations Davis faced, he graduated from West Point in 1936 35th in a class of 276 cadets. He was the first black man to graduate from West Point since 1889 and the fourth black man overall to graduate from West Point following in the footsteps of Henry Ossian Flipper, John Hanks Alexander, and Charles Young. Davis’ white classmates attempted to run him out of the academy, but he persevered and graduated as one of the best cadets in his class, he also gained the respect of his classmates. Davis applied for the U.S. Army Air Corps in 1934 but was denied because they did not accept black men. Davis was commissioned to become a second lieutenant. At the time, Benjamin Davis, Jr., along with his father Benjamin Davis, Sr., were the only two black Army officers who were not chaplains. Davis, Jr. married Agatha Scott in 1936 shortly after graduating from West Point. Later in 1936, Davis was assigned to the 24th Infantry Regiment in Fort Benning, Georgia, one of the original all-black buffalo soldier regiments. Neither Davis, nor his fellow soldiers were allowed to enter the base officer’s club because they were black. Davis began attending Fort Benning’s U.S. Army Infantry School in 1937, he was then assigned the Tuskegee Institute to teach military tactics, a position his father held at Tuskegee. Franklin D. Roosevelt ordered the U.S. War Department to create an all-black flying unit in response to demands for more black men in the military. 1941 was the year the first class of cadets entered their training at the Tuskegee Army Air Field, Benjamin O. Davis, Jr., was one of the initial cadets to enter and graduate class 42-C-SE from the Tuskegee Army Air Field in 1942. Davis graduated from aviation cadet training with Captain George S. Roberts, 2nd Lt. Charles DeBow Jr., 2nd Lt. Mac Ross, and 2nd Lt. Lemuel R. Custis. These were the first four black men to become combat fighter piolets in U.S. military history. Later in 1942, Davis was promoted to lieutenant colonel, he also became the commander of the 99th Pursuit Squadron, the U.S. Military’s first all-black pilot unit. In 1943, Davis’ unit was sent to Tunisia as one of their first missions. The Tuskegee Airman were also involved in a dive-bombing mission against the Germans during Operation Corkscrew, and supported the Allied forces invading Sicily. Davis was instructed to become the commander of the 332nd fighter group, an exceptional all-black air pilot unit. Shortly after Davis began leading his new unit, white senior officers were trying to stop Davis and his unit from being deployed into combat. Davis and his unit were said to be underperforming by their white counterparts. Davis did not sit and allow his men to be insulted and dismissed. Davis was angered by the proposals to dismiss his units, so he held a press conference at the Pentagon presenting all the facts of successes his units were having. The American Army General at the time George Marshall did not dismiss the Tuskegee Airman, but he did hold a review of their performance. The results of the review showed that the Tuskegee Airmen were performing at the same level or better than their white counterparts. In January of 1944, The Tuskegee Airmen were able to defeat 12 German piolets during combat while protecting the Anzio beachhead. Davis led the “Red Tails”, a nick-name given to the Tuskegee Airmen; a four-squadron group on many successful missions penetrating deep into German territory. As time passed, Davis became the commander of more and more all-black air units. One reason was because Davis was an excellent leader, another was no whites wanted to be lead by a black man. Out of the many missions led by Davis, the Tuskegee Airmen were able to shoot down 112 planes, and disabled around 273 planes on the ground, and only losing 66 total planes during the 15,000 missions. Davis personally embarked upon 67 missions flying various fighter planes and receiving awards for his performances such as the United States Silver Star Medal, and the Distinguished Flying Cross award. In 1948, President Harry S. Truman signed the executive order to end racial discrimination within the military. Davis was one of the military officers to help draft the integration order, helping the Air Force become the first branch of the U.S. Military to become fully integrated. After graduating from Air War College, Davis began working at the Pentagon and abroad for a twenty year period. During those twenty years he helped to develop the Air Force’s Thunderbird flight demonstration team. In 1953, Davis became commander of the 51st Fighter-Interceptor Wing in the Korean War. He became the vice-commander of the Thirteenth Air Force and commander of the Air Task Force 13, and temporarily promoted to brigadier general. In 1957, Davis became the chief of staff of the Twelfth Air Force, U.S. Air Forces in Europe in Western Germany. He was again temporarily promoted to major general in 1959 before permanently becoming the brigadier general in 1960. In 1961, he became the director of manpower and organization, and became the deputy chief of staff for programs and requirements. In 1962, he was permanently promoted to major general, and in 1965 he became the assistant deputy chief of staff, programs and requirements. Later in 1965, Davis was again promoted to chief of staff for the United Nations Command and U.S. Forces in Korea. Benjamin Davis, Jr. retired from the military in 1970. In 1998, Davis was promoted to general, U.S. Air Force (retired) by President Bill Clinton. Davis began as a 2nd lieutenant in 1936 and ended as a Four Star General in the U.S. Military. He died on March 10, 2002, but left an honorable legacy and broad shoulders for the next generations to stand upon. To General Benjamin O. Davis, Jr., we proudly stand on your shoulders. J.A. Ward Click here to support the OTSOG book series. References: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Benjamin_O._Davis_Jr. https://www.af.mil/About-Us/Biographies/Display/Article/107298/general-benjamin-oliver-davis-jr/ https://www.military.com/history/gen-benjamin-o-davis-jr.html https://aaregistry.org/story/military-pioneer-benjamin-o-davis-jr/

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Details

Categories

All

Click Here to join our mailing list

|

Contact Us: |

Connect With Us |

Site powered by PIT Web Design

RSS Feed

RSS Feed