|

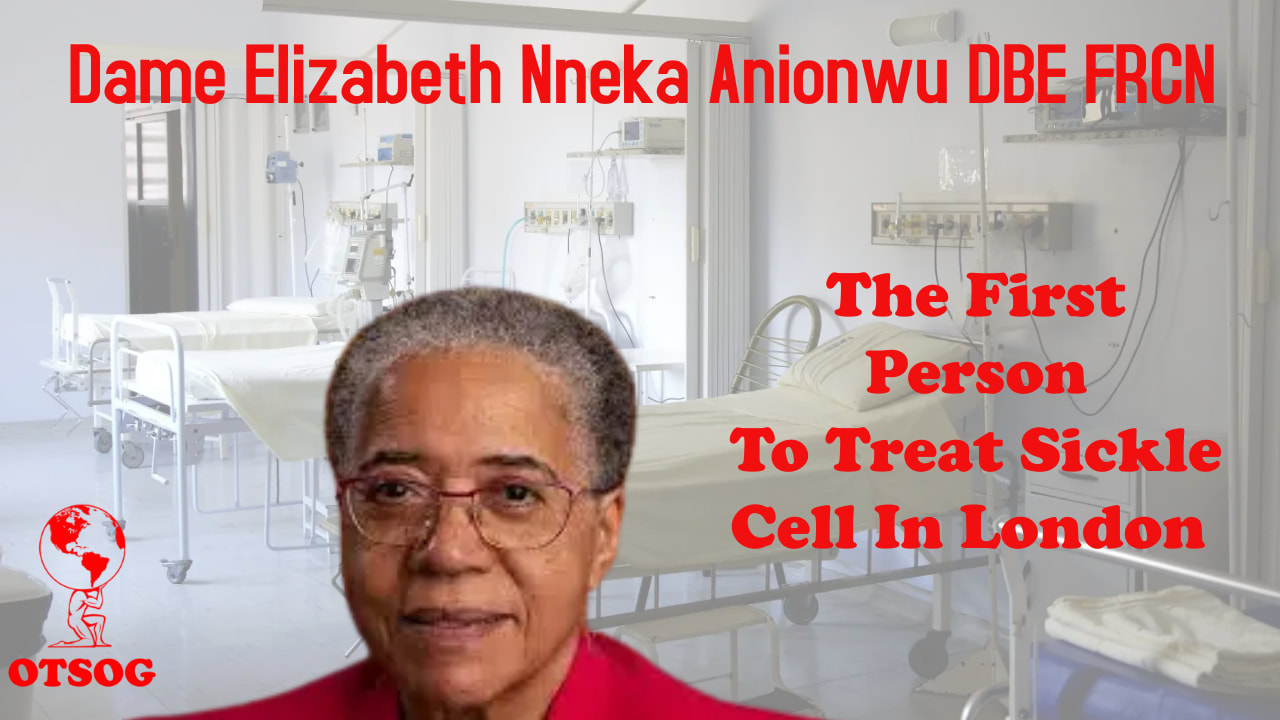

On July 2, 1947, Elizabeth Mary Furlong was born in Birmingham, England. Her mother was an Irish woman named Mary Maureen Furlong studying classics at Newman College of Cambridge University. Her father was a Nigerian diplomat named Lawrence Odiatu Victor Anionwu studying law at the University of Cambridge. Elizabeth’s parents met while attending Cambridge. Mary’s family was a strict Irish Catholic family, because of their values and beliefs, it was difficult for Mary to tell her family she was pregnant by a Nigerian man and unmarried. Once Elizabeth was born, her grandparents took guardianship of her and attempted to present Elizabeth as their own, but her brown skin made it clear she was not their child. Her grandparents were caring for her initially so her mother Mary could continue school, and her father currently was not in the picture. Elizabeth was placed in a boarding school where she experienced harsh treatment by her classmates and the nuns caring for the children. Her skin color and hair made her an outcast among the children, she also had to bear with extreme eczema. The eczema was treated daily with coal and tar paste and wrapped with bandages. Elizabeth could remember being in extreme pain as the bandages were removed for treatment, some of her skin would be removed with the bandages. Of all the nuns that cared for her skin, there was one nun she described as the “nun in white”, who was cautious about hurting Elizabeth as she applied and removed the bandages, in the process, she would tell Elizabeth jokes to distract her from the pain. This experience is what inspired Elizabeth to become a nurse. At the age of nine, Elizabeth’s mother withdrew her from the boarding school and brought Elizabeth to live in her home with her husband. As time passed and Elizabeth settled with her mother and stepfather. Negative judgments about having a mixed-race stepchild began to annoy Elizabeth’s stepfather. The social pressure was said to lead him to become violent within their home. As a result, Elizabeth’s grandparents gained custody while she finished her schooling. At 17, she was accepted to study nursing at the Paddington General Hospital, after several rejections from other institutions. She was an exceptional student who graduated with honors. Elizabeth attributed her rejections to her skin color and not having knowledge of her father. She had to attach a picture of herself to her applications and answer a question about her father’s occupation. As she began attending Paddington she learned that funding was created to aid migrants from south Asia, the Caribbean, and East Africa, but no such thing was happening, so she brought the issue up with her supervisor, and the result was her being given a failing grade for her class. Because of the connections, she made around the institution and around Paddington, London, she was able to be granted an appeal of her failing grade, avoiding her failing the class. Elizabeth also took up a fight against the National Health Services of London for practicing racial discrimination. In March of 1972, Elizabeth became increasingly interested in learning who her father was. She wrote a letter to her mother asking about her father but did not give the letter to her mother. She learned the name of her father at the age of 24. A few months after writing the letter, she approached a man who was a lawyer from Sierra Leone named John Roberts about her father. He did some investigating and found information about her father. He even spoke to her father on the phone. When he revealed this information to Elizabeth, she was shocked to learn that he spoke to her father, thinking he lived in Nigeria. She was even more shocked to learn that her father lived only an hour and a half away from her. The next day she drove to meet her father. She arrived at his residence, approached his front door, and rang his doorbell, when he opened the door they greeted each other with the warmest loving hug. They both were excited to see each other. From that point on, they built a strong and loving relationship. She was able to meet her father’s side of her family in 1973, as she traveled with her father to Nigeria. She was fully embraced by his family. This was the first time in her life that her skin color did not make her an outcast. She felt connected to her father and his family. She felt connected with herself. So connected, she decided to change her name to Elizabeth Nneka Anionwu. Her father died in 1980, but his impact on her life was permanent. Her trip to Nigeria also inspired her to further pursue her career as a nurse. During the trip, she learned that one of her cousins had sickle cell anemia. This was her first time ever learning about sickle cell, but she was curious and wanted to learn more. After returning to London and continuing to practice as a nurse, no one could answer any of her questions about sickle cell because it was a little-known condition at the time in London, mainly because it did not greatly affect white people. She would later begin to gain more information about sickle cell by attending a lunch-and-learn talk by a hematologist named Misha Brozovic. During the talk, she asked numerous questions, so many questions that Misha tracked her down after the lunch-and-learn to ask Elizabeth to join her in working to learn more about sickle cell. Elizabeth and Misha began working together as the only people in the UK seriously interested in studying sickle cell. By 1979, they made great progress, so much progress that they made a two-room hospital into the Brent Sickle Cell and Thalassemia Information, Screening and Counselling Centre. For a period of time, because of the sickle cell center, Elizabeth was the only person in London treating people with sickle cell. Elizabeth and Mish worked for years treating people with sickle cell while receiving virtually no funding because once again, sickle cell anemia was not a disease that greatly affected white people. In 1981, Elizabeth gave birth to a daughter named Azuka. The relationship with Azuka’s father did not last long, so she began raising her daughter as a single parent. Along with raising her daughter, Elizabeth fought tirelessly against institutional discrimination from the National Health Services, while working to find better ways to treat sickle cell. Elizabeth was greatly influenced by the late great Mary Seacole, a Jamaican nurse who established the “British Hotel” which was described as a mess-table and comfortable quarters for wounded soldiers during the Crimean War. Because of the influence of Mary Seacole, Elizabeth founded the Mary Seacole Center For Nursing Practice. A center where black nurses and nurses from all walks of life, can study without discrimination and rejection. The center was also founded to challenge the National Health Service and its discrimination against non-whites. Elizabeth worked as a nurse from 1979 until 2007, the year she retired, but her work would never truly stop. After nursing, she began bringing awareness to the life and works of Mary Seacole, becoming the vice-chair of the Mary Seacole Memorial Statue Appeal. Elizabeth and a committee raised 500,00 Euros in a twelve-year period to create and erect a statue of Mary Seacole at the St. Thomas hospital. During her career, Elizabeth was a senior lecturer for the Institute of Child Health, at the University College London, advocating for people living with sickle cell anemia. She became the dean of the School of Adult Nursing Studies and was also a professor of Nursing at the University of West London. She was a member of the Sickle Cell Society, Nigerian Nurses Charitable Association of the UK, Vice President of Unite/Community Practitioners and Health Visitors Association, and Honorary Advisor to England's Chief Nursing Officer's Black & Minority Ethnic Strategic Advisory Group. She has published over 32 pieces of literature and a memoir titled Mixed Blessing from a Cambridge Union in 2016. In 2001, Elizabeth's career and service in nursing earned her the distinguished honor of being appointed Commander of the Order of the British Empire. In 2004, she received the Fellowship of the Royal College of Nursing, for her pioneering work in sickle cell and thalassemia treatment. In 2007, she was appointed Emeritus Professor of Nursing at the University of West London. She also received a host of other awards and is still being awarded to this day for her pioneering work. To Dame Elizabeth Nneka Anionwu, we proudly stand on your shoulders. J.A. Ward Click here to support the OTSOG book series. References: https://www.theguardian.com/society/2020/dec/10/elizabeth-anionwu-the-cool-black-and-exceptional-nurse-who-fought-to-make-the-nhs-fairer https://www.elizabethanionwu.co.uk/about-me/ https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Elizabeth_Anionwu

1 Comment

The inborn condition can cause extreme pain and organ failure, frequently requiring hospital admissions. One of the first patients to enter into a creative treatment for sickle cell disease on the NHS says she is “elated” to have accepted the “serious” new drug. Loury Mooruth, 62, from Walsall in the West Midlands, is one of the first people to get crizanlizumab at Birmingham NHS Trust - the first new treatment for sickle cell disease in more than two decades. The new treatment, crizanlizumab, will lessen the persistent pain, trips to A&E and will desperately making better the patients’ standard of life. Conversing after her first treatment, Loury said: “Sickle cell has been part of my whole life. People notice you and think you look best, but they don’t perceive the pain and the strain along with the several trips to A&E. Patients with sickle cell suffer from monthly events, making it hard for people to go on in their jobs or other daily activities.

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

Details

Categories

All

Click Here to join our mailing list

|

Contact Us: |

Connect With Us |

Site powered by PIT Web Design

RSS Feed

RSS Feed